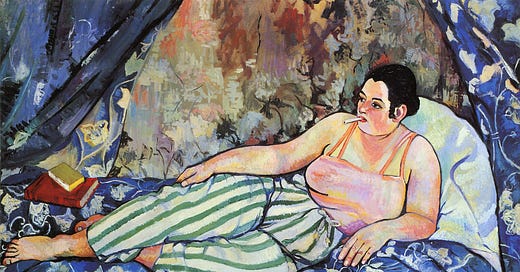

One of Suzanne Valodon’s most famous paintings is The Blue Room, painted in 1923 and which, according to Wikipedia, features a “startlingly contemporary lounger”. The Blue Room, according to art critics, is a rejection of a tradition of draping nude Venii (I assume this is the plural of Venus and you can’t stop me) over velour bedspreads, where they become objects to be ogled by concupiscent 16th-century teenagers.

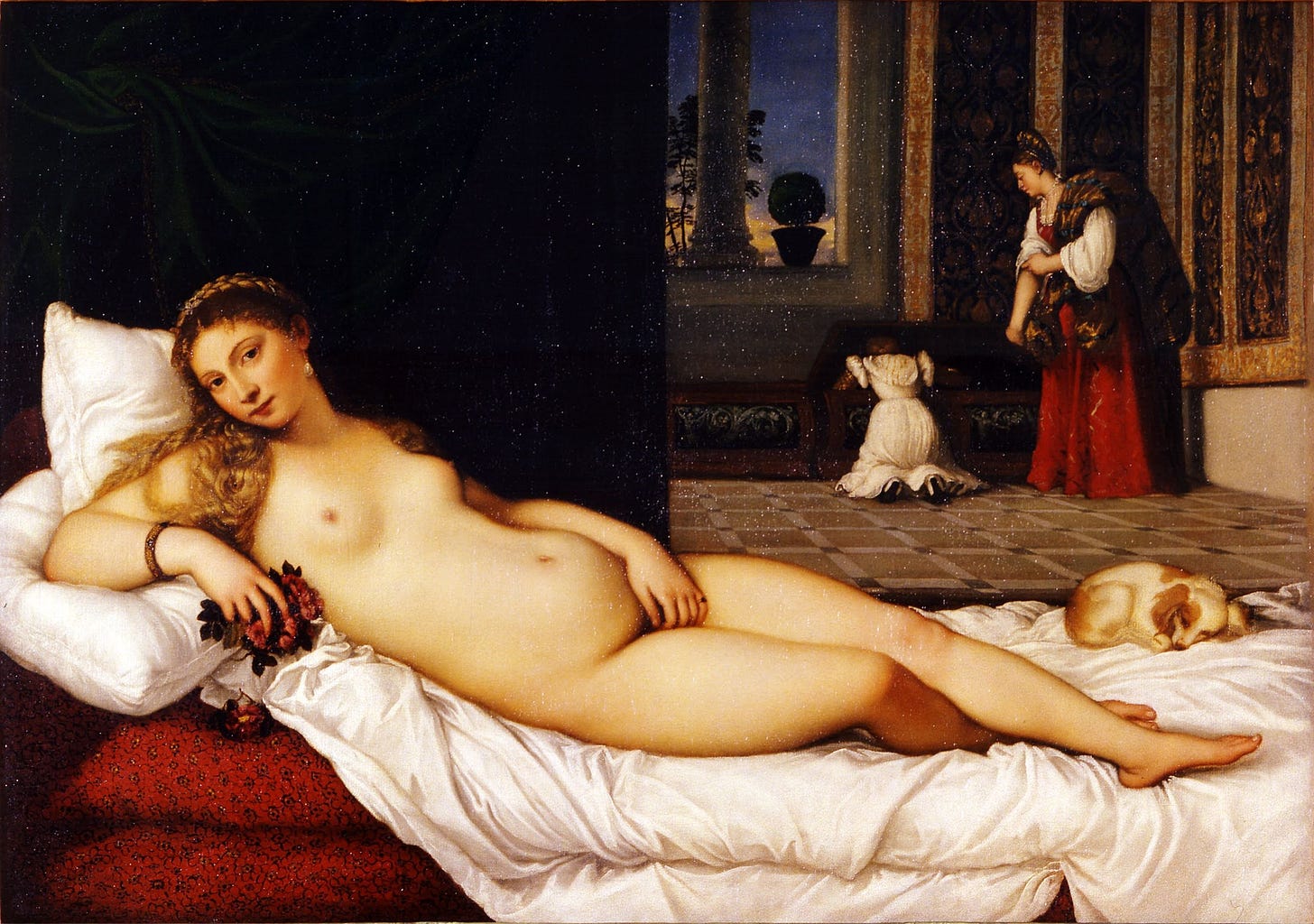

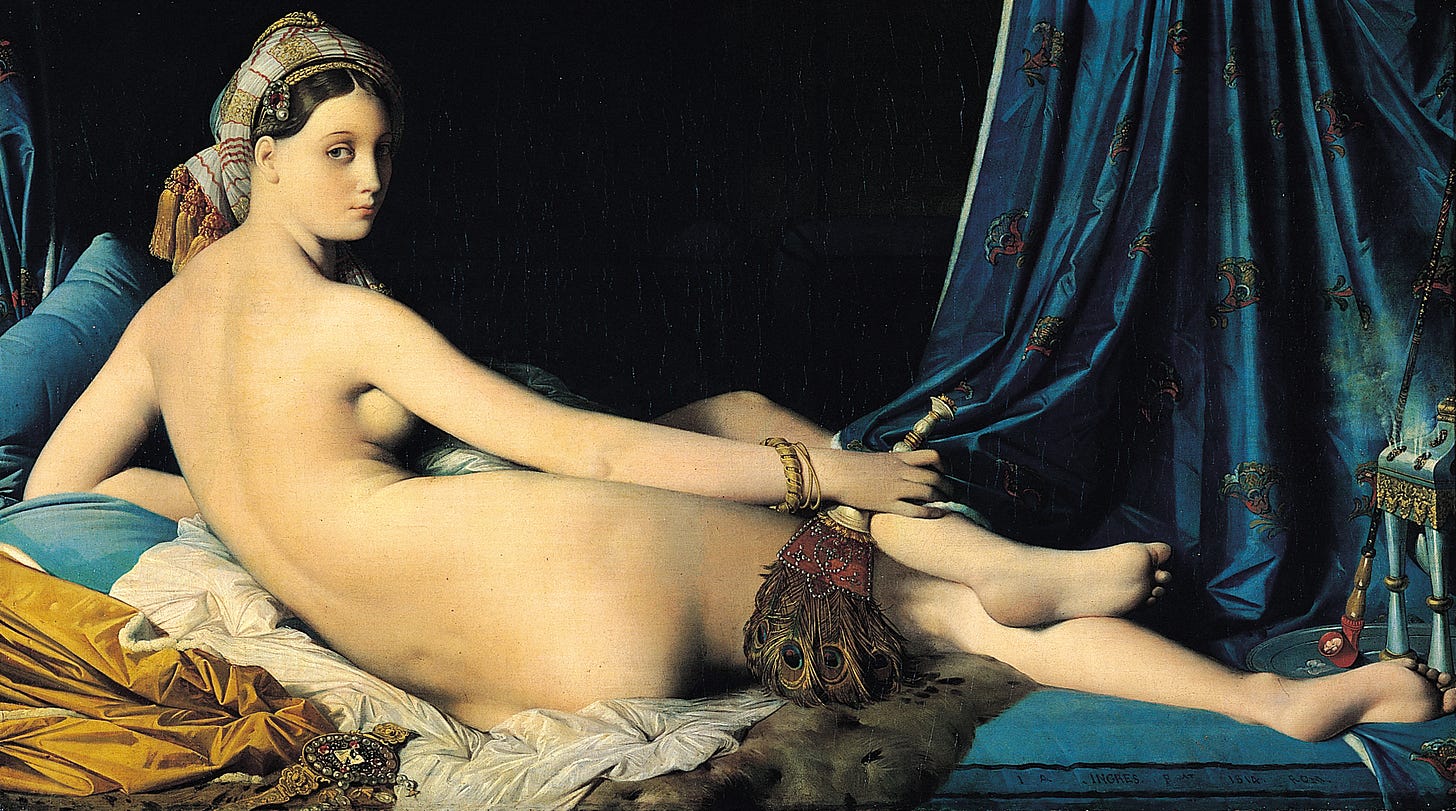

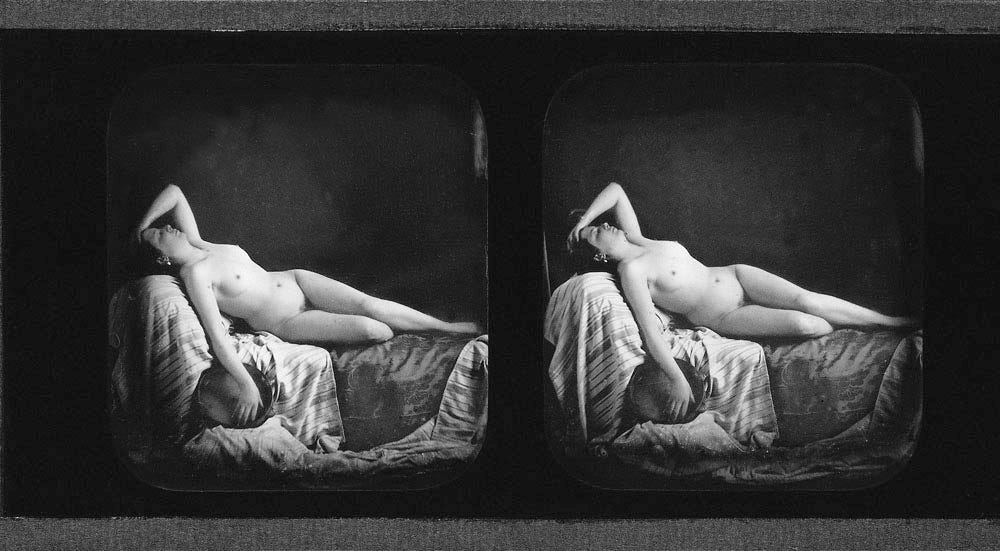

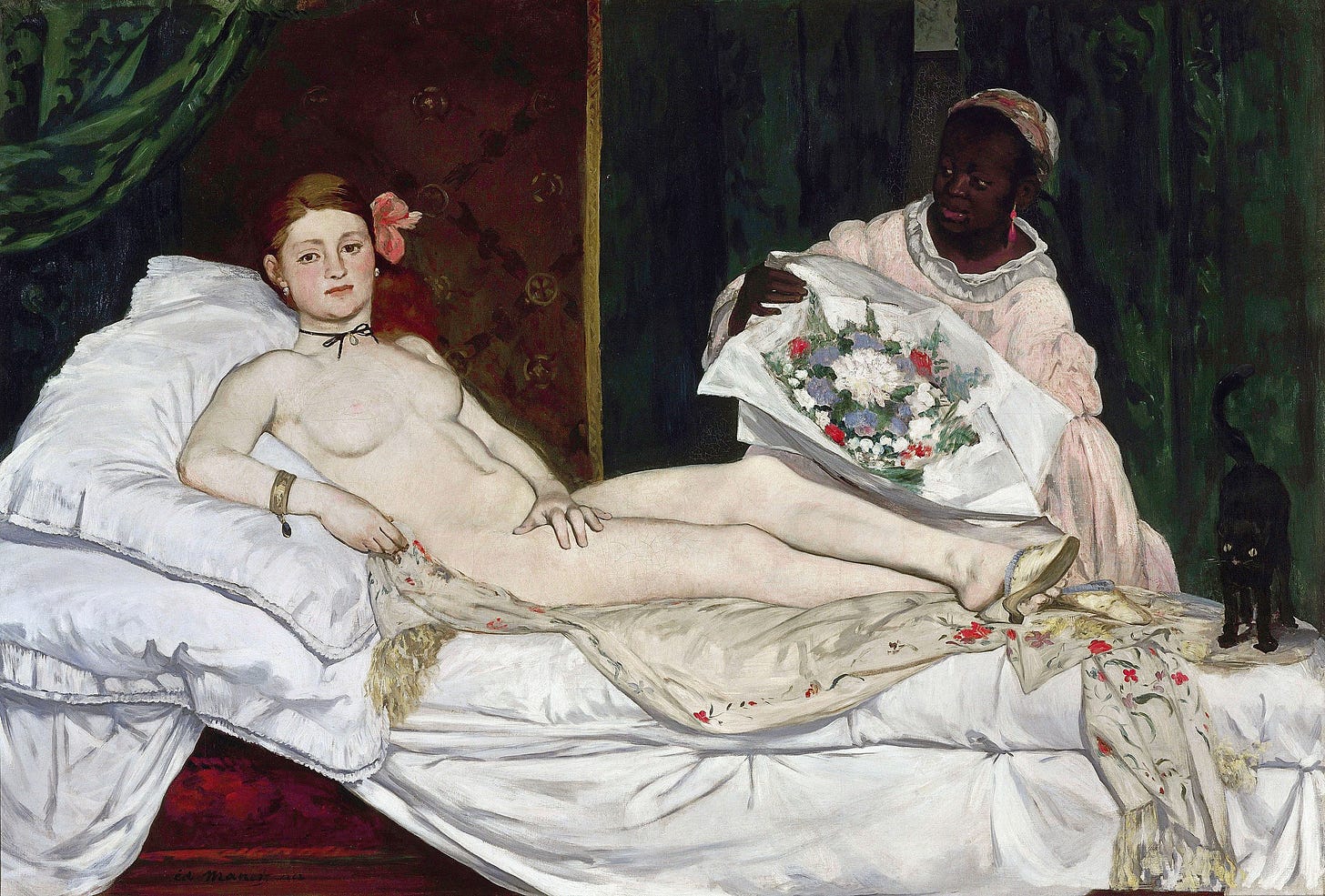

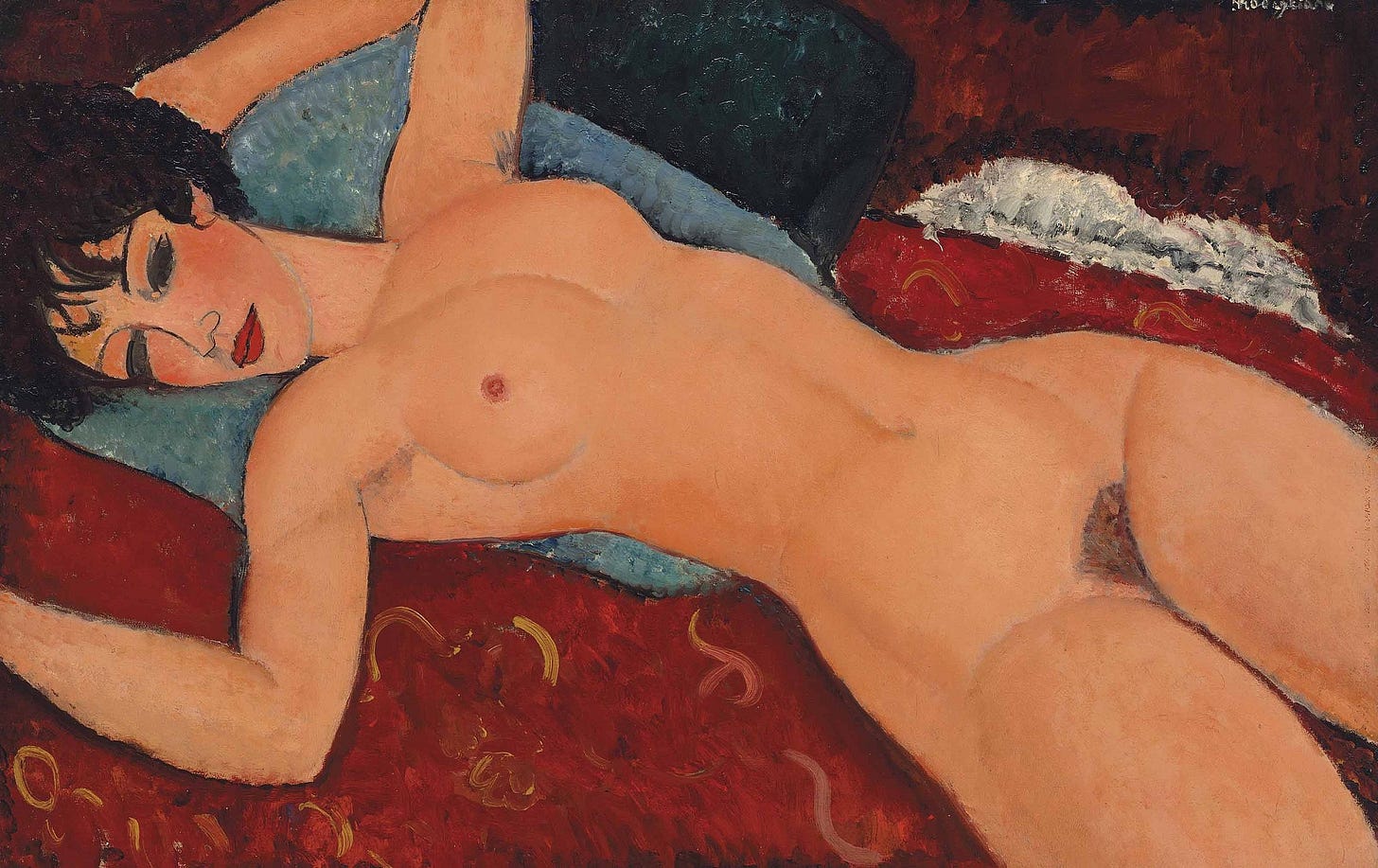

Valodon, being a woman, unsurprisingly rejected this notion and painted the central woman of The Blue Room in such a way that she reclaims the space for herself, and periodicals of the early 20th century record the distress of horny teenagers everywhere. Below is the complete lineage of this tradition, finally laid out in full* by my painstaking research and hard work (*disclaimer: I may have missed several hundred artworks).

Note that only Valodon’s model reclines right to left. I assume this is because Suzanne Valodon was enthralled by the recent publication of Noether’s theorem in 1918, and decided to show that symmetries imply conservation laws in art too, and not just because I’ve conveniently ignored other paintings that don’t go left to right.

During my minutes-long lucubrations of this topic, one puzzling question kept emerging for me: Why are some artists so much more highly regarded than others?

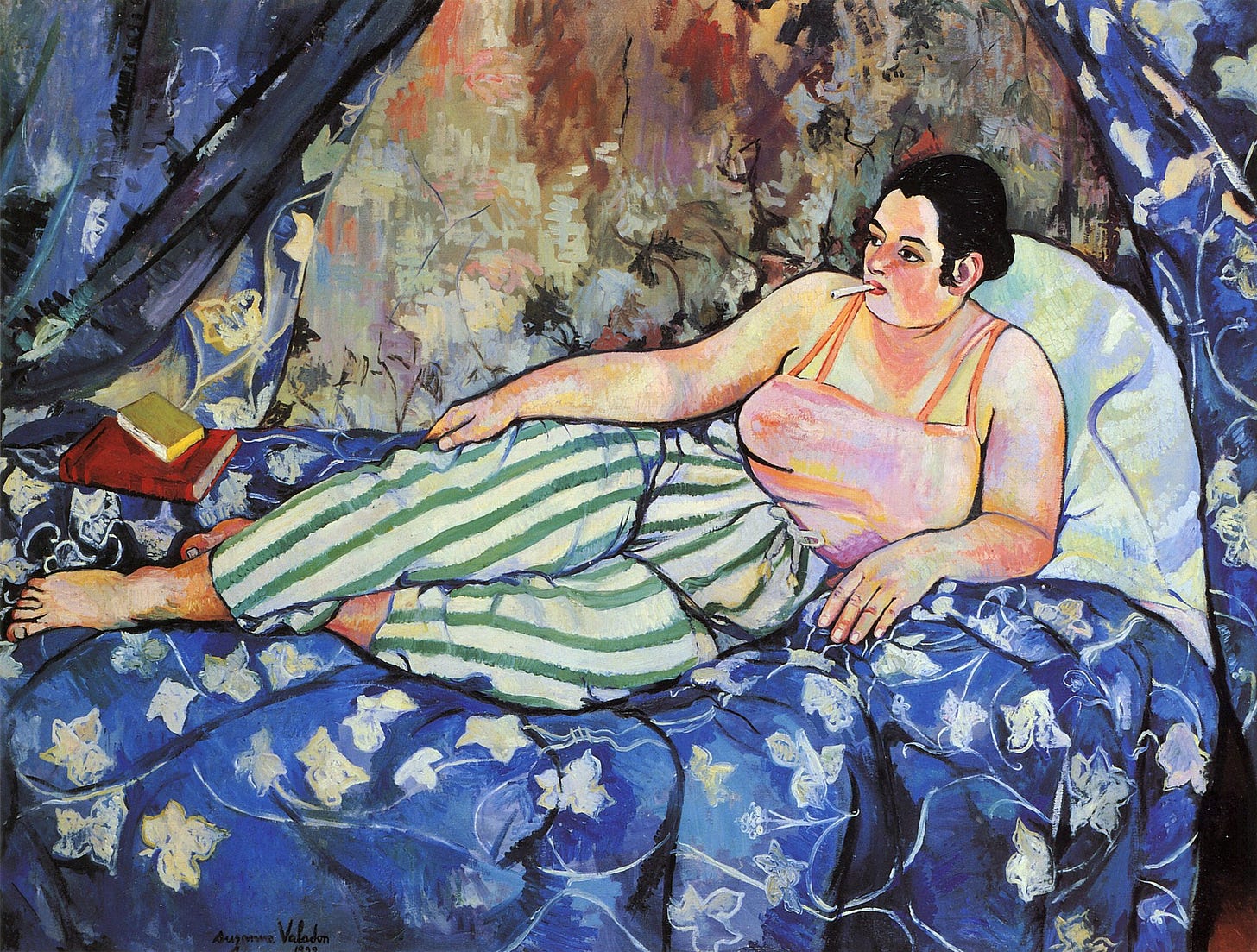

I think most people reading this will never have seen Vecchio’s Resting Venus before I put it in my now-iconic list. I had to mudlark through the filthy riverbed of esoteric Wikipedia to dredge it up.

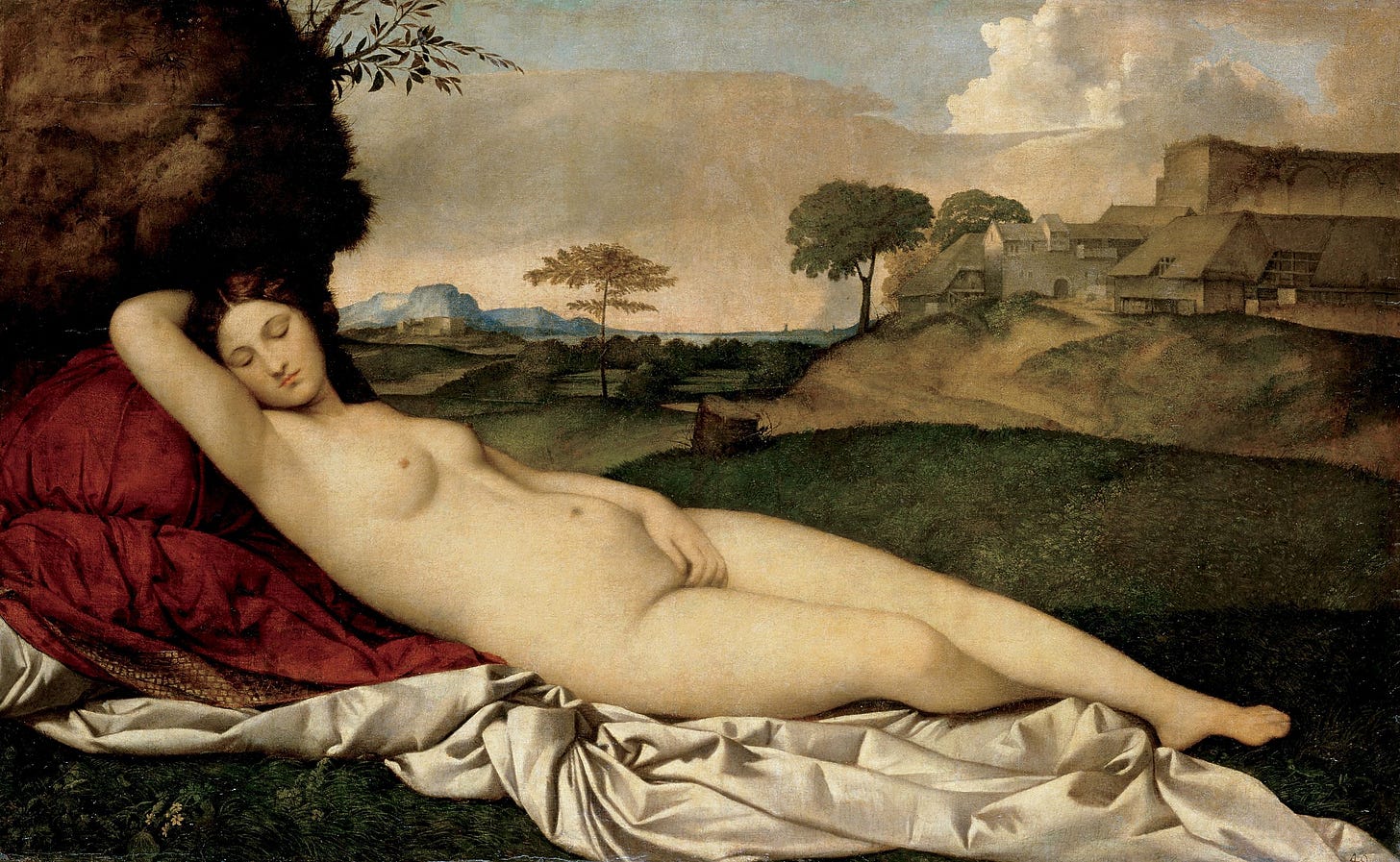

But I think most people reading this will have almost certainly seen or heard of Titian’s Venus of Urbino. Titian is excellent, dude. Many of the later images in this list, particularly Olympia, are explicit homages to the Urbino painting.

But why? Why is one so much better known, and better regarded, than the other?

Here are a number of possibilities that occurred to me in the space of five minutes, and I refuse to do any more thinking than that:

Titian’s Venus has some intrinsic artistic quality, likely due to some sort of Faustian pact Titian made with the Painting Devil.

Titian pioneered the form of the Venus with Giorgione, and has first-mover advantage which allowed him to establish his Venus-moat and prevent new competitors from getting Venus-market share.

Commentators decided early on that Titian was better and we’ve never looked back. Giorgio Vasari, an opinionated and embittered 16th century artist, accomplished in his own right, has a bunch of exalted dithyrambs about the talent of Titian in his Lives of the Artists. This was likely good for Titian’s street-cred.

Titian has more stuff, and its altogether more impressive, and so his name pops up more, and so then Victorians on their Grand Tour to Venice would exclaim, “I say, take me to your Titians” and the Italians would look blankly and point towards all the overpriced cigars they could buy.

Titian’s Venus of Urbino exists in a reified and hierarchical power structure that seeks to repress the new in favour of the old, and elites prefer things this way so they never change.

You may be sat there, smugly thinking to yourself, “Well of course it’s Option 1! Just look at them!” You may have other opinions. I like Option 1. Titian’s Venus looks better to my dullard eye than Vecchio’s Venus, even if the second one sounds cooler to say. Let’s make sure we put the bike pump before the bike tyre. We may already think Titian’s Venus of Urbino is better because, paging Danny Kahneman, we have strong biases towards things that we are familiar with. To actually explain why it is better is something of an artform, and we to do that, I think we maybe have to discuss ‘beauty’ as a concept. At length. Forgive me.

BAD BIBLICAL ART

There is a general sentiment among most reasonable people who look at art that no art is really better than any other art. But there is also a general sentiment among those same people that some art is a lot better than other art.

Let’s leave aside the hackneyed debates about modern art for a second. Differences in quality without real differences in form occur a lot in paintings of the Bible. Restrictions in the canon of what can be painted mean that we can look at direct comparisons.

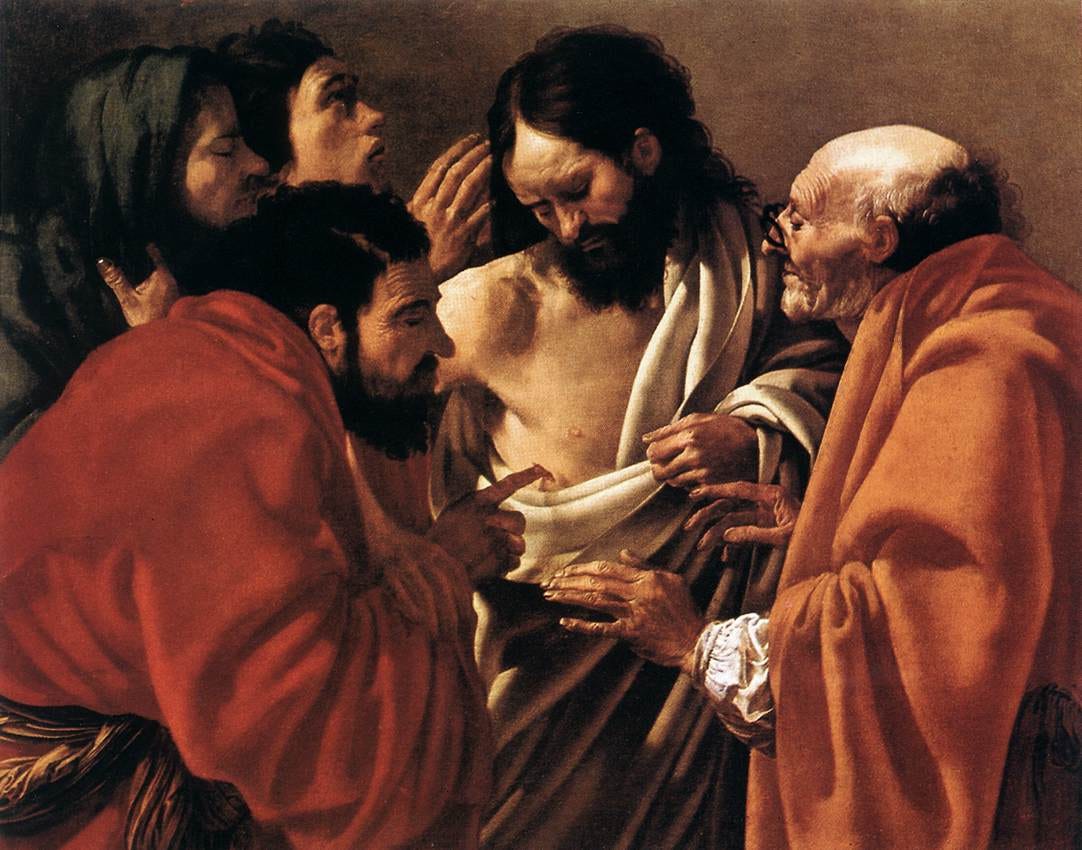

For instance, The Incredulity of Saint Thomas - one of Caravaggio’s masterpieces - is beautiful. Look how visceral the penetration of the finger is! It makes me squirm. The wrinklage (now a word, you’re welcome) on the faces of the disciples propels them into the tension of the scene - Christ grimaces, a literal and metaphorical grimace against those who have challenged his divinity.

Here is one of the Dutch Caravaggisti (Caravaggio’s followers), Hendrick ter Brugghen, covering the same subject matter:

Would anyone pick the second over the first? Perhaps for the old spectacled dude, whose hands look so fragile you just want to hold and protect them, or for the man who bears a strange resemblance to Pete Davidson in the top left of ter Brugghen’s work. But Christ’s head feels strangely proportioned, and the image is less cohesive, less directed to the central subject matter. The colour of the background distracts from the scene, rather than enhancing it. It feels less beautiful.

When we look at the minor figures of the Bible, who only those generally regarded as lesser painters really cover, the lack of quality is more evident. Here’s Jael, a heroine in the Hebrew bible’s Book of Judges, as painted by Jacopo Amigoni:

For context, Jael’s main thing is that she kills a guy called Sisera with a chisel. The dialogue is really riveting:

And Jael said, “Strengthen in me today, Lord, my arm on account of you and your people and those who hope in you.” And Jael took the stake and put it on his temple and struck it with a hammer.

And while he was dying, Sisera said to Jael, “Behold pain has taken hold of me, Jael, and I die like a woman.”

And Jael said to him, “Go, boast before your father in hell and tell him that you have fallen into the hands of a woman.”

But the painting isn’t much better, at least for me. The precursors of great art are here - the subject matter, the poses of the figures - but there is a flabbiness to it all, a lack of depth. The whole thing feels like its been washed with a pastel filter which kills all life within.

PINPOINTING PRETTY

I suppose the question I’m really driving at here is about beauty. Is there an inherent beauty that certain artworks, or objects, or even people have?

The answer seems to be yes. Babies prefer looking at attractive faces from within 72 hours of being born. It goes further than that. Three to four month year old human babies prefer looking at more attractive tigers than less attractive tigers. During pre-cognitive processing there is some mechanism that draws us to more beautiful and attractive things.

When I say ‘pre-cognitive’, I’m referring to the idea that human perception is composed of stages. To explain briefly and, let’s be honest, badly; there is a first stage of cognitive processing which is unconscious - objects are selected for our attention by various brain processes. Objects here could be visual, or auditory, or tactile. I’m using ‘object’ as a cheat word. Those objects are then processed in a second stage where you get to actually think about the object you are paying attention to. There’s also possibly a third stage where the conclusions of the first and second stage are wrapped into a new understanding of the object.

If you think about that object again, the first and second stages of your processing will have been altered by that third stage. This may just make it more prominent in your field of view, as in the pop-out effect, where you notice objects more that you have just been talking about, or it may have much deeper ramifications.

One obvious explanation is that we prefer attractive faces because we are evolutionarily programmed for reproduction, and beauty is indicative of someone who will make a good mate. So why do we prefer attractive tiger faces? Perhaps beauty cannot be so easily condensed into the evolutionary narrative. Beauty may be related to sexual selection, but it feels cynical to limit it entirely to some pure evolutionary instinct. To live that way removes some of the joy of life.

And what of pure beauty? Of beauty that offers little but satisfaction? The solitary pleasure taken in enjoying a beautiful work of art, or listening to a song, or the pleasure mathematicians seem to get from their funny squiggles?

As the astronomer Mario Livio writes:

“Since the laws of nature have the elements of beauty engraved in them, it should come as no surprise that aesthetic principles played a major role in the shaping of our thinking about the origin of the universe.”

Charles Darwin, who uses the word ‘beauty’ on average once every seven pages in On the Origin of Species, was well aware of the ineffable nature of the problem:

How the sense of beauty in its simplest form - that is, the reception of a peculiar kind of pleasure from certain colours, forms and sounds - was first developed in the mind of man and of the lower animals, is a very obscure subject … how the sense of beauty in its simplest form was first acquired - we do not know.

What is beautiful is often said to be culturally bound; ‘beauty is in the eye of the beholder’ is transfigured into ‘beauty is in the culturally conditioned eye of the beholder’. But as a general rule, this is implausible. Humans from very different walks of life agree on the beautiful. Culture shapes an already prominent impulse.

Amazonian tribesmen were shown images of the Western world - the moon landings, our treatment of the elderly, our wars, our treatment of animals. They were generally repulsed - landing on the moon is considered a violation, not a beautiful act, because for these tribesmen, the moon is sacred.

Yet, when they are shown a clip of Maria Callas singing Bellini’s ‘Casta Diva’, they are awed. One says, ‘This music is not our culture. We do not know what it means. We can only watch and listen. But we are touched by it.’ Another: ‘I find it overwhelming. Without understanding her, we sense that there is something sacred there.’

This is not to say that culture plays no role. From Robert Sapolsky’s Behave:

V. S. Naipaul, in his book “Among the Believers: An Islamic Journey”, describes hearing rumors while in Indonesia that when a paramilitary group would arrive to exterminate every person in some village, they would, incongruously, bring along a traditional gamelan orchestra. Eventually Naipaul encountered an unrepentant veteran of a massacre, and he asked him about the rumor. Yes, it is true. We would bring along gamelan musicians, singers, flutes, gongs, the whole shebang. Why? Why would you possibly do that? The man looked puzzled and gave what seemed to him a self-evident answer: “Well, to make it more beautiful.”

Instead, it seems that decisions about much of what is beautiful exist pre-cognitively. We are drawn to things that are beautiful before we start making rational judgments about them. This is not to say that power-structures and hierarchy play no role in shaping beauty, but that beauty is not entirely subordinate to such external forces - it is perfectly capable of defending itself.

Often, it seems that our pre-cognitive thoughts are subject to the whims of the society that we live in. The pre-cognitive realm is often considered more basal or more animalistic - something to be silenced and challenged by our more rational selves. Our judgments are attributed to some nebulous cultural power, that shapes all of our tastes and ideas. But this doesn’t seem correct.

This force likely does exist, but it doesn’t control us. We actively carve out the things that we consider beautiful, and we are the architects of our own tastes. The final construction of our taste never quite matches our design, in the same way that no building ever matches its blueprint. One can be taught to perceive certain things as beautiful, but only slowly, and never against a person’s will. As Immanuel Kant put it in the Critique of Aesthetic Judgment:

If we judge objects merely in terms of concepts, then we lose all presentation of beauty. This is why there can be no rule by which someone could be compelled to acknowledge that something is beautiful. No one can use reasons or principles to talk us into a judgment on whether some garment, house, or flower is beautiful. We want to submit the object to our own eyes, just as if our liking of it depended on that sensation.

The difficulty comes from the gestalt nature of beauty. Beauty exists purely in the relations between different components of a thing, but awareness of those relationships serves only to undermine the beauty of the whole.

Elaine Scarry writes in On Beauty and Being Just:

Beauty causes us to gape and suspend all thought ... but simultaneously what is beautiful prompts the mind to move chronologically back into the search for precedents and parallels, to move forward into new acts of creation ... to bring things into relation. It is not that we cease to stand at the centre of the world, for we never stood there. It is that we cease to stand even at the centre of our own world. We willingly cede the ground to the thing that stands before us.

Beauty forces us to give way. In the words of Paul Delany:

“The power of beauty may always have some flavour of tyranny: but we are more ready to embrace the tyrant than to protest against the capriciousness of her rule.”

There are some thoughts on beauty. Kant wrote that “there is no science of the beautiful”, and he may have been right in the late 18th century. But I’ll finally get one over on the Königsberg King in the near future when I talk about some of the neuroscience on perception and beauty. But for now, I’ll leave you with what I think is an ugly painting about an ugly subject - a tax collector. Maybe you’ll find it beautiful. I doubt it.