I’m going to clarify at the top that I’m not a geneticist. If you want to read stuff by actual geneticists, please go ahead and read books by geneticists. I’ve written this because this book is fairly controversial, and I thought I would clarify why some of that controversy exists for people who like me, want to understand more but might have time to read full books by geneticists. I will explain terminologies and ideas as we go.

1.

So there’s two possible outcomes to any debate about genetics; either we decide that genes cause everything, that the environment is basically secondary to the overwhelming might of the zygotic advance, and that we should restructure our whole society around these depressing but true facts. The other is to say that genetics may matter, but it’s too hazy as a field to make conclusions out of, and since we’ve tried for many years and most of the progress we’ve made has been used to inflict untold pain on disadvantaged peoples, maybe we should just ignore the whole thing.

Obviously, these are not the only two outcomes, but they do point to the problem of talking about genetics - unless you very aggressively say “we can’t do much with this”, people are probably going to call you a racist. I’m not a geneticist, and I found myself rebutted firmly when I discussed the conclusions made in The Genetic Lottery with academics outside the field of biology.

Kathryn Paige Harden is a geneticist, and Ruha Benjamin writes that she engages in “savvy slippage between genetic and environmental factors that would make the founders of eugenics proud”. I’m going to try and summarise the argument she makes, and then we’ll look at what other people have had to say.

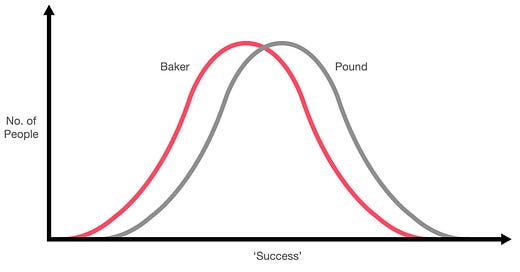

To explain Harden’s fundamental argument, imagine two nuclear families: the Pound family, where the father works as a high-level consultant and the mother works as an investment banker, and Baker family, where the father works as a cleaner and the mother works in a warehouse. There are two sets of children; the Pound children, who are packed off to a nice Clarendon school, and the Baker children, who go to their local state school.

Most people accept there will be significant environmental differences between these two families. No matter how hard the Baker children work, the Pound children are going to have access to better resources at home and in school, and better tuition. The Pound children are more likely to be able to go to elite universities, or start their own businesses, or go into show business. The Baker children will be less likely to do so. They still can do so, but they are disadvantaged from doing so by their environmental circumstances. Their set of ‘good’ outcomes get shifted left on a normal distribution of outcomes, through no fault of their own. If you multiply this out a million times, you get a normal distribution that might look something like this:

Baker children can still achieve the same outcomes as the Pound children, but less of them do so. One of the key tenets of redistributive social programs is that we should act to help Baker children preferentially so that their outcomes are more similar to the Pound children. There are a lot of ways to complicate this. If we add in historical oppression of particular social groups, and a limited set of public resources, suddenly the redistributive equations about who ‘should’ get what are intensely difficult to resolve. Let’s leave that aside for now.

Harden’s main argument is that there is an additional layer of advantage given to some children. This is genetic advantage, which comes from having genes associated with outcomes that are desirable. Some people are taller than others, and height is associated with a higher lifetime income. Genes that code for height are in this sense desirable, because most people consider a higher income as desirable. Harden discusses a series of findings that show certain genes are associated with increased years in education, which in turn are associated with higher average salaries.

Genes can’t just be simply associated with years in education, can they? Tiny pieces of genetic code that differ from person to person seem unlikely to help somebody stay in school for longer. Harden and her fellow researchers rely on Genome-Wide Association Studies (GWAS), which look at single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs). These are areas of genome that commonly differ between people, and that ‘tag’ other variations in the genome, so if you measure a large series of someone’s SNPs, then you can extrapolate from that to make conclusions about other parts of the genome.

The word ‘extrapolate’ may ring false alarm bells; certain combinations of genes are often more likely than chance to be inherited together, and such genes are said to be in linkage. Linkage means that certain genes are more likely to be correlated with each other, which is known as linkage disequilibrium. Traits like height are said to be polygenic - associated with many thousands of genes - meaning that it is difficult to measure them. GWAS allows us to do that. You end up with thousands of SNPs that vary between people, and depending on the genetic combination you have at a certain point, those SNPs can be said to predict further educational attainment.

Various authors have sat down with genetic data from hundreds of thousands of people to over a million people, and looked at which SNPs correlate with staying in school longer. If we imagine a fictional SNP, X, and we see most people who are in school for more than twelve years have X, whereas most people who stayed in school for less than six years don’t have X, then X is assigned a high polygenic weighting. If an SNP has a low correlation with additional years of schooling, it is assigned a low weighting. Combining these weightings gives you a polygenic index, where you can plug in a new person’s genome, and the polygenic index could be said to be predictive of how many years that person will stay in school.

Throughout this essay, I’ve tried to put scare quotes on any time a genome is rated by a polygenic index, because the genes are only ‘good’ in the sense that they lead to culturally desirable outcomes. Harden cites Sandy Jencks’ famous hypothetical, where an authoritarian society bans people with red hair from receiving an education. Suddenly, genetic differences related to red hair are genetic causes of educational attainment, and they would stop being causes if the policy were rolled back.

There are further problems that arise from this. For instance, our education system is constantly changing, and so genetic variants that are associated with success in it are likely to have some level of fluidity as well. Harden doesn’t mention this in the book and I assume most scientists who believe in this work think that this rate of social change is too slow to matter. People who don’t agree with Harden’s arguments probably think it does matter, but more on that later.

Harden:

In samples of White people living in high-income countries, a polygenic index created from the educational attainment GWAS typically captures about 10-15 percent of the variance (R² = 10-15%), in outcomes like years of schooling, performance on standardised academic tests, or intelligence test scores. (source)

This is just a correlation, but Harden also cites this paper from Funder and Ozer which gives us some context for this correlation:

The tendency for antihistamines to relieve allergy symptoms (R² = 1%).

The tendency for men to weight more than women (R² = 7%)

The tendency for places at higher elevations to be colder (R² = 12%)

The tendency for taller people to weigh more (R² = 19%).

The tendency for children born to rich families to graduate from college at higher rates (R² = 11%).

R² means ‘variance explained’, but it doesn’t explain anything. It’s just showing how strongly one variable is related to another variable. As Funder and Ozer point out:

Some readers, traditionally trained to think of .30 correlations as “explaining only 9% of the variance” might be surprised to learn that an effect of this size will yield almost twice as many correct predictions as incorrect ones.

So if these claims are right, then certain children will have an additional advantage, because their genomes are associated with the ability to stay in school for longer. Harden stresses that we don’t know the mechanisms here. We have some ideas - many of these genes may instantiate certain types of neuronal development that allow faster brain network connectivity, or the ability to inhibit distraction better, or the ability to shift between tasks more effectively. Fully confirming these sorts of ideas is difficult.

2.

Time for some reviews! Firstly we have a sociologist, Callie Burt, who argues:

While mentioning that these findings ‘hold up’ when using sibling studies, which control for the potential environmental confounding variables by examining differences between siblings who share such environments, she never acknowledge[s] that the variance explained/effect size drops in these sibling studies from 10-14% to <3%.

This isn’t cited, but assumed, while elsewhere in her review she niggles at Harden for not including proper citations. I’ve tried to verify this claim, and the closest I’ve found is this paper, which mentions that an educational attainment polygenic score is associated with 0.6% and 3% of the variance of Big Five personality measures, rather than years in school. But that paper also says this:

In a representative UK sample of 7,026 children at ages 12 and 16, we show that we can now predict up to 11% of the variance in intelligence and 16% in educational achievement.

So I don’t think I’m looking in the right place. But Kevin Bird’s review makes a similar case that Harden is overstating the numbers:

While it’s true that polygenic scores from sibling analyses resolve substantial problems that sometimes create inaccurate associations between DNA and a phenotype, Harden fails to mention several key differences between these sibling-based methods and other genomic or twin-based methods.

It is rarely stated clearly that these family methods produce much smaller estimates of genetic effect, often nearly half the size as population-based methods, making the 13% variance explained by current education polygenic scores a likely overestimate. Harden also fails to mention that a commonly used method employed does not fully eliminate the problems from population structure or that estimates from siblings can still include confounding effects that create correlations between genes and environment.

Harden argues that the effect is likely to be larger than 10-15% (nobody seems to be using the same numbers). This is because twin studies generally show higher estimates of heritability (usually around ~40%), and so Harden devotes a section of her book to trying to explain this ‘missing heritability’, between the 10-15% from GWAS studies and 40% from twin studies.

It’s hard to accept Bird’s review at face value because it’s so actively hostile. If your children need help learning to count with numbers smaller than five, just ask them to search through Bird’s review for the positives.

Bird hates, HATES, Harden’s approach to heritability, for reasons that mostly seem to boil down to the fact that she apparently misinterprets Richard Lewontin, or something. Innocently enough, when reading the book I got the sense that Harden likes Lewontin, she just disagrees with Lewontin’s views about the possibilities of behavioural genetics. If you read Kevin Bird talk about Harden and Lewontin, you end up reimagining the Tyson-Lewis press-conference as the Harden-Lewontin press conference.

I mentioned heritability above. Heritability does not indicate what proportion of a trait is determined by genes and what proportion is determined by environment. Saying something is 60% heritable means that 60% of the variability (not the whole) in that trait in a population is due to genetic differences among people. This is an actively difficult concept to wrap your head around.

I find it’s useful to think about heritability along with the phrase ‘relative to your peers’. Height is somewhere around ~80% heritable, so 80% of the variability within a population’s height is explained by genes. My height is 80% explained by my genes - relative to my peers. Some populations will be taller or shorter than other populations as a general rule, but the heritability number is for explaining variance within any given population. You cannot transfer ‘heritabilities’ from one population to another, as Robert Sapolsky explains at length in Behave. Just because a trait is 80% heritable in one population does not make it 80% heritable in another. Height is likely to be 80% heritable though. That’s been done that with loads of populations.

To make it more confusing, sometimes papers talk about heritability at different ages. For instance, that height paper says that the heritability of height increases as people get older. This is because your genes can take time to kick in and make you tall.

The concept is useful yet terrible, and everyone in the field knows it’s useful yet terrible, and yet they do nothing about it. Let’s move on.

3.

In a review of Harden’s book, M.W. Feldman and Jessica Riskin compare Harden’s assertions to those of Francis Galton, whose ‘Known For’ section on Wikipedia has eugenics as top billing, right next to behavioural genetics. The equivalence they draw is similar to Ruha Benjamin above, where they equate Harden’s belief in a normal distribution of personality traits to eugenics:

“This polygenic index will be normally distributed,” Harden continues, now disguising an assumption—that there are intrinsic cognitive and personality traits whose distribution in a population follows a bell-shaped curve, a founding axiom of eugenics—as an objective fact.

Believing that people are normally distributed in some traits does not make you a eugenicist. Plenty of clinical psychologists believe IQ is a valid construct that is normally distributed, and they use it to measure people with dementia as a way of measuring their decline. They aren’t eugenicists, they’re just trying to help people. They may be wrong about whether IQ is normally distributed, or whether IQ is a good proxy for intelligence, but drawing an equivalence with eugenics here is in poor taste. But Feldman and Riskin are aggressive in their dismissal of what we can learn from behavioural genetics, as Richard Lewontin, Leon Kamin and Steven Rose were before them.

Stuart Ritchie argues that Feldman and Riskin’s response is anti-scientific. Their argument, as he phrases it, is that there’s no point studying genetics, because it is descended from eugenic practice (that the words are near anagrams probably doesn’t help this association), and any answers it finds will be necessarily tainted.

The more reviews I read of this book, the more confusing and entrenched and frankly, dangerous ideas I find in strange corners of the internet. I am broadly in favour of the concept of Ruling Thinkers In, the concept that we should evaluate people for their good ideas and discard their bad ones. But this argument has a glaring flaw because it neglects the main reason that people pay a lot of attention to bad ideas - they’re often dangerous.

People have been sterilised because they were deemed ‘feebleminded’, and this was acceptable to the logic of some scientists at the time. This is a far cry from the examples given in ‘Ruling Thinkers In’, which emphasises Isaac Newton’s work on Bible codes as an example of possible bad ideas.

I was planning to do a compare and contrast of two reviews from opposite ends of the political spectrum, but when I typed in ‘right wing review of The Genetic Lottery’ I found this guy and felt a bit sick. I only mention him because one of Kathryn Paige Harden’s main criticisms of the approach of progressives to genetics is that they spend a lot of time trying to ignore the field, and in doing so they open the door for a whole suite of white nationalists to attempt to align genetic research with their political views. If progressives did engage with genetics, this might happen anyway, what with white nationalists committed to being nasty pieces of shit, but hey, it might help.

If you are interested in a right-wing perspective, Razib Khan reviews the book for UnHerd. Khan has been linked to the alt-right and scientific racism, although he seems to be someone we should rule in, not out. The phrase ‘uncomfortable truth’ is bandied around a lot by racists, but Khan’s research may be a genuine example. Michael Eisen puts this in a clearer way:

“[Khan is] a very, very bright geneticist [who] understands modern human population genetics as well as almost anybody.” Eisen disagrees with many of Khan’s conclusions, and he said that Khan had “allied himself, in one way or another, with people whose views are not just repugnant — they’re just wrong. I think many of the things Razib writes highlight the implications of modern genetic research in ways that people find upsetting, but aren’t necessarily wrong.” (emphasis mine)

This is the problem with much of modern genetics research - the implications are scary, and difficult for people to grapple with - and this is why it’s worth discussing The Genetic Lottery.

For a left-wing perspective, here’s a savaging that The Genetic Lottery received from Kevin Bird, a Professor of Evolutionary Biology (mentioned above).

One of the fundamental differences in general sentiment between the two ends of the political spectrum seems to be that those on the right tend to believe that behavioural genetics is handing us ironclad laws of nature about who we are as people, and those on the left tend to believe that behavioural genetics is useless, or that those ‘ironclad’ laws are a lot looser and subject to a greater extent to environmental change than the right would have you believe.

Harden occupies the middle ground, where she believes fervently in the possibility of behavioural genetics to enhance our understanding of people, but doesn’t share the right-wing intransigence towards rectifying those natural inequalities. She is anti-eugenic, and massively in favour of more equitable distributions of social resources. I think, broadly, that any other characterisation of her stance is unfair. Her mistake/insight/genius/insanity is to believe that behavioural genetic research can be used in order to aid this position without being captured by hostile interests.

4.

Another review, this time originating from more neutral territory. Graham Coop and Molly Przeworski point out that the children who have such genetic advantages are not likely to be randomly distributed, because people do not mate randomly, known as assortative mating.

This is something that Harden is, uh, well aware of? This is discussed in her book, and I’m not really sure why was part of their critique. The main point they want to make however, is that polygenic scores are difficult to draw conclusions from, and that Harden is guilty of trying to make the case that these scores are useful for evaluating outcomes within-populations, but not evaluating outcomes between-populations. They make the case that this is a ‘have your cake and eat it’ scenario:

In our view, these instances reflect a more general tension in the book, which arises from trying to have it both ways: to argue that PGS [polygenic score] for educational attainment provide interpretable and meaningful predictions of inter-individual differences that reflect underlying genetic causes, yet to claim that they have no validity beyond hypothetical population boundaries. As we have laid out, we believe instead that current PGS for educational attainment are neither interpretable nor particularly meaningful.

There’s that “it doesn’t mean anything” critique again! We’ll come to that in a second. Here’s the second half of their concluding critique:

But we currently understand next to nothing about the causal paths from GWAS findings to educational attainment, notably the extent to which they include analogs of Jencks-style “red hair effects” and the legacy of accumulated indirect effects. That may not matter when PGS are to be employed as a statistical tool in the study of the impact of social interventions, but it matters greatly when they are used to elucidate, let alone redress, social inequalities.

This is a legitimate critique, but it isn’t really a disagreement? As I mentioned above, Harden says similar things here and throughout the book. I’m not sure why geneticists are all spoiling to fight each other all the time.

Back to the cake and eating it. The difference between having a genetic study and using a genetic study to inform policy is sizeable. Both Harden and Stuart Ritchie argue the same line of rebuttal - that there are different standards of evidence for genetic arguments than there are for environmental ones. Harden regularly brings this sort of problem up in the book. People will believe that behaviours are genetically influenced depending on both the behaviour and the context. And people will differ greatly on their willingness to assign genetic influences at all depending on their own belief systems.

Conservatives, for instance, are less likely than liberals to attribute outcomes to genetics, particularly for moralised outcomes, such as sexual orientation or addiction. If people believe that someone should be punished, as a series of court trials have shown us, they will readily dismiss genetic or neuroscientific information. Harden also retorts, in her reply to Coop and Przeworski, that if this Chetty et al. study from 2016 has similar standards of evidence and was broadly accepted. To elaborate, Coop-Przeworski, among others, deny that these results are particularly meaningful, and Harden retorts, among others, that if the results had come from a different literature to behavioural genetics, they would be regarded as meaningful.

Let’s go back to the Pounds and the Bakers. Now we have a case there are not only environmental advantages in play, but also genetic ones. It is here that Harden deploys her best chart, taken from this paper:

EA Score, for reference, is educational attainment score, in this paper equivalent to a polygenic score. Look at the Pound family (or Father Inc. Quartile 4, as they’re known on the street) on the right of those different income levels. They’re killing it! Even when they have children who have the ‘worst’ polygenic index for graduating college, those children are graduating from college at a similar or higher rate to those with much ‘better’ polygenic scores coming from poorer backgrounds.

If you believe in meritocracy and if you think that genes = talent (two big ifs), this chart should outrage you. It clearly shows kids with traits that would let them succeed in education being failed by a system that supports rich children.

5.

Every so often a certain news story repeats itself. A rich celebrity, or business leader, or influencer, makes a comment like: “I've worked my absolute a** off to get where I am now.” That was Molly Mae-Hague, a successful instagram influencer, who took a lot of heat for the Thatcherite tone of her comments.

Kim Kardashian infamously made a similar comment:

I have the best advice for women in business. Get your f*cking ass up and work. It seems like nobody wants to work these days.

She later apologised for this comment, but even in her apology did not shy away from her core message, that she has earned her position by hard work:

Having a social media presence and having a reality show does not mean overnight success. And you have to really work hard to get there, even if it might seem like it’s easy and that you can build a really successful business off of social media and you can if you put in a lot of hard work.

There is an almost infinite list of such ideas drifting through the internet, all revolving around the idea that *anyone* can work hard, and it’s the difference in the amount of hard work that people do that justifies wealth inequalities.

The traditional left-wing counter-argument to these stories is to label such ideas as ‘Thatcherite’, and to point out that those at the top sit in a nexus of socioeconomic privilege and advantage which is difficult for them to see, adroitly summarised in this cartoon. That nexus of privilege enables these people to work hard, and to work hard at things that enable bigger rewards, such as unpaid internships, or orchestrated sex tapes feat. Ray-J (click the link, I dare you). The point about privilege is legitimate, but if we accept Harden’s conclusions, and again, that’s a big ‘if’, we should also make a secondary point, about the inequity of genetics.

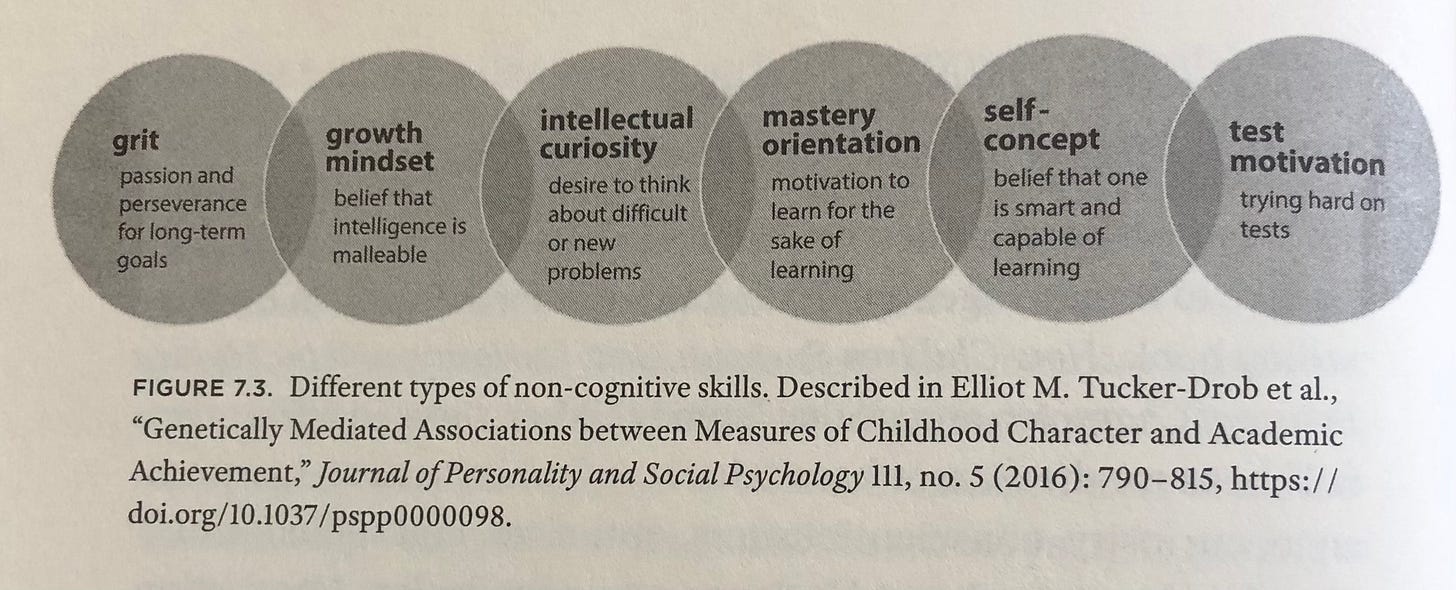

Geneticists and neuroscientists spend a lot of time debating a set of skills known as non-cognitive skills. The title is a misnomer, because most of the genes and neurons involved in the development of these skills are instantiated in the brain. You’ll almost certainly recognise some of them because they spend a lot of time in the public eye being pushed by various psychologists and educational reformers:

These are taken from a paper by Tucker-Drob et al. (et al. here including, the protagonist of this story, Kathryn Paige Harden) on non-cognitive skills. ‘Hard work’, the concept that the influencers above love so much, is perhaps most closely reflected in ‘Grit’, or the ability to keep going even while surmounting difficulties. But all of these non-cognitive skills are likely to be relevant to the ability to work hard.

Remember when I talked about heritability above? Your skills are about to be put to the test. Tucker-Drob et al. suggest that all of these skills are moderately heritable (~60%) in the same way that cognitive skills are moderately heritable (~50-80%). All of which suggests that a significant amount of your ability to concentrate, your ability to focus, your ability to sit there and not get distracted by Candy Crush, or Facebook, or a slot machine, or a bird, or Superman, is genetic in origin. Or rather, your ability to focus better - relative to your peers - is partly genetic in origin.

To put it yet another way, differences between people in their ability to work are not immune to the randomness of genetics. Genetic and environmental randomness play large roles in determining people’s skillsets, and importantly, their ability to work hard, sustain their concentration and avoid distractions. Tucker-Drob et al. focus on the ability to succeed in academic environments, but there’s no reason the ability to apply yourself in a disciplined manner wouldn’t be present in other places. Justifying wealth inequalities off the back of these skills is thus a deeply damaging idea. Life isn’t as simple as saying “I work hard, so I deserve this”.

6.

It’s not really fair, is it? People have much higher levels of natural talent that are squandered by their lack of income. In fact, the whole system isn’t really fair. If some people are arbitrarily predisposed to having certain abilities by their genome, why should we discriminate on the basis of those differences? Harden’s answer, in the second half of the book, is to grapple with the question of luck, invoke the Rawlsian Veil of Ignorance, and argue that we should study genetics in order to push for redistributive policies for those who have ‘worse’ genomes for the outcomes we consider desirable.

I liked this part of the book the most, perhaps because redistribution based on inequity is something that appeals to me, and finding new ways to look at and think about inequity is cool.

This is from a Vox article by David Roberts on luck:

These recent controversies reminded me of the fuss around a book that came out a few years ago: Success and Luck: Good Fortune and the Myth of Meritocracy, by economist Robert Frank. It argued that luck plays a large role in every human success and failure, which ought to be a rather banal and uncontroversial point, but the reaction of many commentators was gobsmacked outrage. “On Fox Business, Stuart Varney sputtered at Frank: “Do you know how insulting that was, when I read that?”

And he continues:

[Acknowledging luck] just means that no one “deserves” hunger, homelessness, ill health, or subjugation — and ultimately, no one “deserves” giant fortunes either. All such outcomes involve a large portion of luck.

There are studies that suggest that conservatives are less likely to attribute success to genetic luck than liberals. This is perhaps strange to consider, given right at the start I said that conservatives are more likely to treat genetic papers as final determinist assays of the human condition. I’m not sure what explains this dissonance. It seems difficult to me to believe that genetics is determinist and that you also have high agency when it comes to success in school or business.

The main takeaway for me from The Genetic Lottery was that the role of luck deserves a more thorough treatment in our politics. But this case is very hard to make politically, because to do so, you have to rely on messaging that is essentially anti-aspirational. To say we should re-assign our society’s wealth because of the determinism of genetics and environment is a difficult argument to communicate to voters.

I recently attended a talk by Lea Ypi, a Professor of Political Philosophy at LSE, who discussed a totally different topic (her book is about the fall of Communist Albania). She emphasised that politically, much of our messaging can focus on blame - it is this person’s fault that they’re homeless, or that they’re ill, or that they’re uneducated - but it should focus on responsibility - it is our responsibility to give them a house, or give them medicine, or educate them.

Genetics has become another strand in this long-winding debate about our responsibilities to others in our societies, and Harden makes the slightly Panglossian case that we should use it, and use it to do better for other people. Remember, genes are only good or bad depending on their environment, and we can change the environment much more easily than we can change the genes.

If we were to say that people with genes which made it harder to get through schooling should get more classroom assistance, that would likely be a good thing, on the face of it. The problem is that such policies require a form of classifying people by their genome, and are thus likely to be difficult to implement. But Harden is right to insist that we should at the very least have a conversation about it, if only to reclaim the space from those who are currently doing so.