Catching up with the Neanderthals

Even though I walk through the valley of the shadow of the new man, I will fear no evil

Firstly, hello to all of my new subscribers. Thanks for reading my review of a book about bees, and thanks for subscribing. If you are an old subscriber and you don’t know what I’m talking about, I submitted a review of Lars Chittka’s The Mind of a Bee to a book review contest and it was shortlisted, so I’ll post that here next week. This blog is about cognition and memory, and today we’ll be coming at it from the perspective of our ancestors.

I read The Neanderthals Rediscovered recently, a book which focuses on trying to revamp the image of Neanderthals. One of the best parts, that the authors clearly took great pleasure in writing, was a list of possible reasons why Homo sapiens were able to outcompete the Neanderthals. Choose your fighter:

Obviously the Dog-Human alliance is the best theory, because it makes it sound like the neanderthals unsuccessfully tried to woo the leaders of the Dog Clans of the North, but were beaten out by modern humans, who offered better diplomatic gifts like Scooby Snacks and toy bones.

What do we know about Neanderthal extinction? Neanderthals were present in Europe until about 40,000 years ago, when they reached the maximum range of their expansion, the Siberian caves in the Altai mountains. Then they disappear really quickly, as the authors of The Neanderthals Rediscovered, Michael A. Morse and Dimitra Papagianni, write:

It is helpful to imagine the entire course of human evolution, from the appearance of the first Homo habilis in Africa to the present, as taking place over the course of a single day. For convenience, let us start the clock with midnight representing 2.4 million years ago, which is within the range of when the genus Homo is thought to have emerged. In this time-compressed day, with each hour representing 100,000 years, humans left Africa at dawn, around 5 to 6am.

They first arrived in Europe at noon, already at the halfway point since the appearance of the human line. In what was probably a subsequent out-of-Africa expansion, Homo heidelbergensis or its ancestor species spread from Africa to Europe at dusk, just before 6 pm. By 9pm the Neanderthals had evolved in Europe and were manufacturing Levallois tools, while their counterparts in Africa were making similar technological advances.

At around 10.45pm an early form of Homo sapiens arrived in the Middle East. By 11.20pm Neanderthals had become the predominant type of humans in western Asia and were steadily pushing eastwards towards Siberia, which they reached around 11.30pm. By 11.40 pm, just twenty minutes before present, all traces of the Neanderthals were gone. When the Last Glacial period ended at 11.54pm, modern humans were on the verge of establishing long-term settlements and inventing agriculture.

One of the staple theories about this rapid extinction is that Homo sapiens were smarter than Neanderthals. Once you assume this, it’s easy to come up with a set of reasons why they were able to outcompete the Neanderthals, as John Hawks points out here. He argues that even if we know neanderthals were different to us cognitively, that doesn’t suggest that they were stupid and we were smart. It’s not a good assumption to base a theory off.

We do know that there were structural differences between our skulls and neanderthal skulls. Neanderthals had what is known as the occipital bun, a protrusion at the posterior part of the skull. Some humans still possess this, but it is relatively abnormal. The occipital lobe processes vision, so it may have been the case that neanderthals had better visual processing than modern humans, on the basis that more allotted brain space usually equals better processing.

So we found a sizeable difference between Neanderthal brains and our own brain. You know what comes next:

The idea here runs something like: more visual processing → less other processing → less social processing → social processing is very important for accelerating modern humans into our current form → neanderthals get outcompeted.

But brains are pretty malleable, so they can fit into different skulls if they need to. Neanderthal brain volumes are not significantly smaller than humans. There are many people alive today, even after we’ve evolved for another 40,000 years, who have smaller brains than neanderthals. And a larger occipital bun doesn’t necessarily mean that neanderthals were worse at socialising.

Perhaps we should ask how the Homo genus evolve advanced cognitive abilities, but firstly, let’s outline what we mean by advanced cognitive abilities:

Growth in diversity of artefacts

Rapid increase in how fast artefacts change

Earliest appearance of stuff that is definitely art and personal ornamentation

Oldest indisputable structural ruins

Oldest evidence of humans living in the coldest parts of Eurasia

Oldest evidence for transport of large quantities of stone over long distances

Oldest evidence for fishing

The classic example given is that of the Löwenmensch (Lion-man) figurine, sometimes called the Hohlenstein-stadel Lion Man. This guy, seen below, is about 35,000 years old and is among the earliest clear human-made representations of things that don’t exist.

No other animal has ever come close to creating a representation of a thing that doesn’t exist, and early hominin species didn’t either. The neanderthals wore eagle talons as jewellery, but that’s not a representation of something that does not exist.

What we do know is that we gained potent thinking powers, and that the neanderthals could have possessed them as well, but we have little proof. That doesn’t mean neanderthals were like the caveman stereotype - there’s a high likelihood they had a form of language, but our thinking capacities go beyond language. The main candidate for a type of brain activity that allowed for modern humans to dominate the world is complex episodic future thought, and it is not obvious when this developed in humans or if it developed in neanderthals.

Where did the neanderthals go? There’s a decent chance that neanderthal populations could have naturally died out, given that many of the tribes were small, and there was significant inbreeding. There was also some interbreeding between Neanderthals and modern humans, because there is about 2% Neanderthal DNA in Eurasian and Australasian genomes, although it goes down to about 0.5% in African genomes. There’s also a chance that modern humans pushed neanderthals off their land, and their populations were small and dispersed enough that this doomed them. We may never know.

So how did we get potent thinking powers, that may or may not have extended beyond those of the neanderthals? Theories abound here, and given our lack of evidence for many of them, it is difficult to pick a winner. One of the problems is that modern humans evolved across Africa, and then spread outwards, but Africa is the hardest continent to do paleoarchaeology in, because of lack of funding and violence (on the continent generally, rather than between paleoarchaeologists). There are plausible origin stories for modern humans in Eastern Africa, but a southern origin, for example in the Makgadikgadi basin, seem to be more widely accepted.

One major theory is the social brain hypothesis that I outlined very briefly when discussing occipital buns. This is the brainchild of Robin Dunbar, and argues that primates have large complex brains in order to deal with their large complex social systems. In primates, group size is a monotonic function of brain size (i.e. primates with larger social groups always have larger brain sizes). But this isn’t true in other mammals or in birds, where large brains are associated with differences in mating patterns, with larger brains being found in species that have pair bonding.

Dunbar suggests that primates may have used the brain structures and patterns associated with pair bonding and generalised them to broader relationships, and in doing so enabled larger social groups, and that social cognition is complicated, and thus encouraged the development of complex cognition. We rarely notice the demands of social cognition because we are so habituated to it, but having a conversation is mentally taxing.

If you are ever at a party, take a minute to watch groups change. No group will ever go above five people talking to each other as a group for an extended amount of time (unless one person is lecturing the group or telling a story), without splitting into smaller subgroups. This is because talking to people is hard and we have limits on the number of people we can track in a conversation.

Another theory suggests that types of foraging and ecological constraints played a significant role in the development of human intelligence. Chimpanzees and bonobos are both closely related to modern humans, but chimpanzees have longer foraging ranges and are less risk-averse. In tightly controlled spatial memory tasks, chimpanzees have a better performance than bonobos, and they have a much stronger spatial memory overall. In this model, risk-taking in foraging develop into longer term cognitive powers, such as episodic future thought, which allow for better planning.

These debates both dance on the surface of another debate: When did advanced cognitive abilities develop?

There are two broad theories. The main criteria that these theories have to explain is that complex behaviours seem to emerge rapidly about ~45,000 years ago. The first theory suggests that some change occurred at this time which caused rapid developments in behaviour and thought. The second theory thus suggests that between roughly 200,000 years and 100,000 years before present, a suite of cognitive abilities developed in tandem across different parts of Africa, so that the foundation for the ‘cognitive revolution’ is actually in place long before it occurs.

Experts disagree when exactly the size of the hominin brain stabilised, but most agree it occurred at least 200,000 years ago, and no earlier than 600,000 years ago. You will have noticed that throughout this piece there is a large range whenever I give years. You’re probably also thinking that paleoarchaeologists could surely stop bickering for enough time to narrow it down a little more, but the reasons for the difficulties are multifarious. As Chris Stringer notes:

There is growing evidence for the precocious appearance during the Middle Stone Age of aspects of modern human behaviour such as complex technology and symbolism (McBrearty & Brooks 2000; Henshilwood & Marean, 2003), yet the evidence is often disparate and discontinuous. For example, what are we to make of archaeological sequences where typical Middle Stone Age assemblages are first succeeded by apparently 'advanced' Howiesons Poort artefacts, and then in later deposits, typical Middle Stone Age material returns (Wadley, 2001; Wurz, 2002)?

He also points out:

We are perhaps misled by recent human history, where information storage in spoken, written or electronic form means that useful innovations are rarely lost, and the growth of ‘cultural' knowledge is incremental or even exponential.

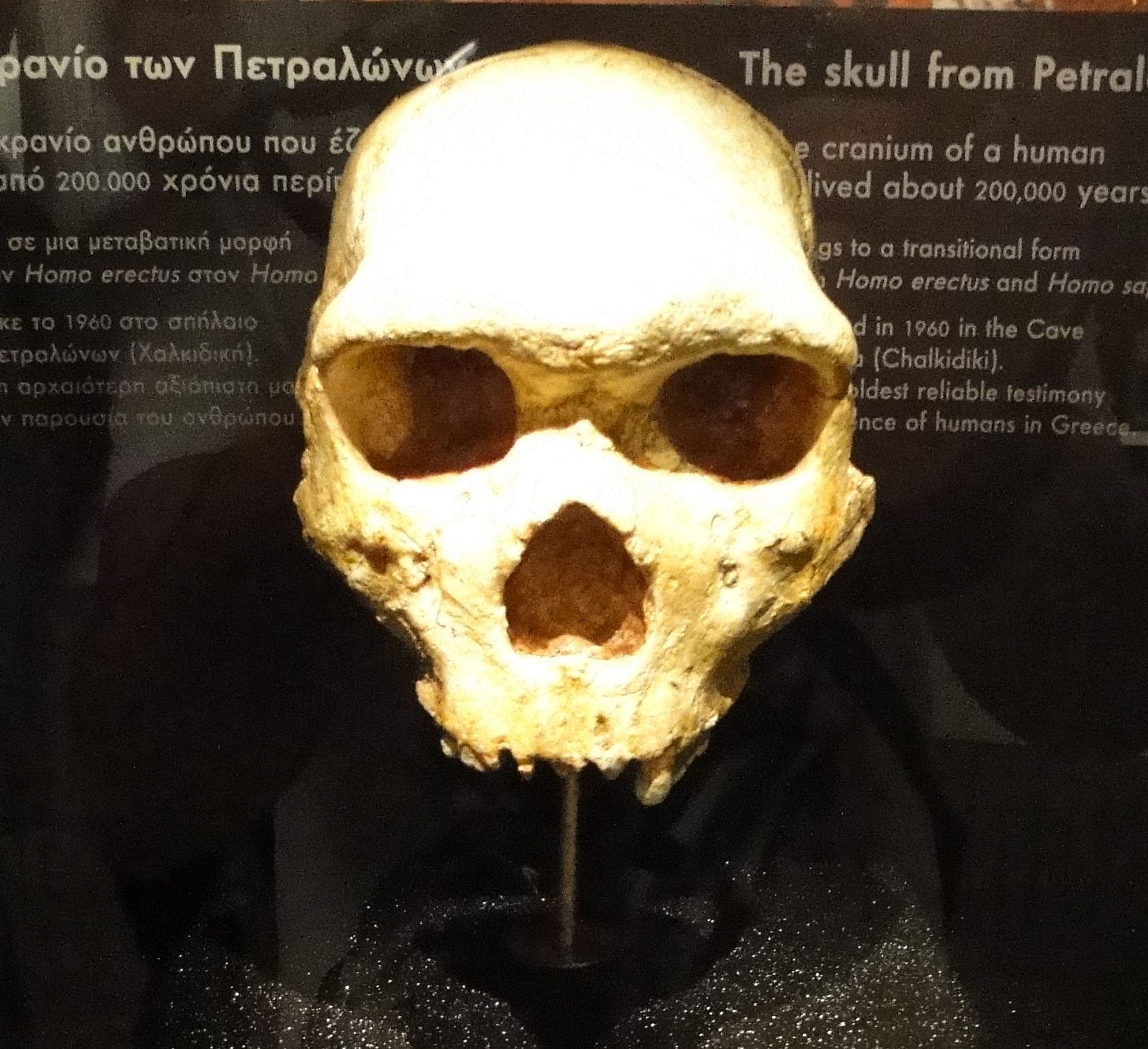

There’s also a prestige to having important sites located in your country, so you get cases like the Petralona skull, where a Greek archaeologist called Aris Poulianos found a skull, claimed it was found implausibly deep in the cave sedimentary layers, and then stated it was ~700,000 years old and that it was a new species of Homo that he’d discovered.

This was totally incompatible with theories about how humans dispersed out of Africa, and most archaeologists now think that this skull is part of the Homo erectus genus and that it is about 160,000 to 240,000 years old.

So what happened with our brains? Why are we so “special”? A new theory, espoused by Murray, Wise and Graham in The Evolution of Memory Systems, argues that three significant changes occurred to create explicit memory in humans. Explicit memory, in their theory, separates us from animals, and it allows us to rapidly develop into modernity. Explicit memory is, broadly, what H.M. lost when he lost his memory. It is the intentional recollection of past concepts and ideas.

They naturally have to dedicate a large amount of space to defending the claim that animals do not have explicit memories, which I won’t go into here.

But the main thrust of their argument runs something like:

Hominins began to use pre-existing parietal-prefrontal networks in order to solve reasoning problems and perform what is called multiple-demand cognition - the cognition involved in picking task-relevant stimuli, separating tasks into stages and responding to changing task contexts.

The lateral temporal cortex evolved from representing resource indicators to represent generalised concepts that we have in semantic memory.

The granular prefrontal cortex developed a high-level representation of self as a response to complex social systems.

These changes produce the ability to higher levels of representation, and produce “explosive generalisation” across cognitive domains. The development of complex parietal-prefrontal networks means that they can intervene when specialised brain regions are struggling, and synthesise a solution at the top-level.

Steps 2 & 3 are then critical because they operate together; once I can represent myself in my own memory, I can support the kind of brain networks required to know things, and in turn operate on those known things.

This is obviously controversial, because it partly disguises a theory of consciousness as a theory of explicit memory. But a comprehensive theory of explicit memory, at least from what I understand these authors mean by explicit memory, would likely hint at the evolution of consciousness. Learning that the way that we experience consciousness might have begun as several cognitive systems rapidly developed and began to overlap would not be particularly surprising, but it would be nigh on impossible to prove.

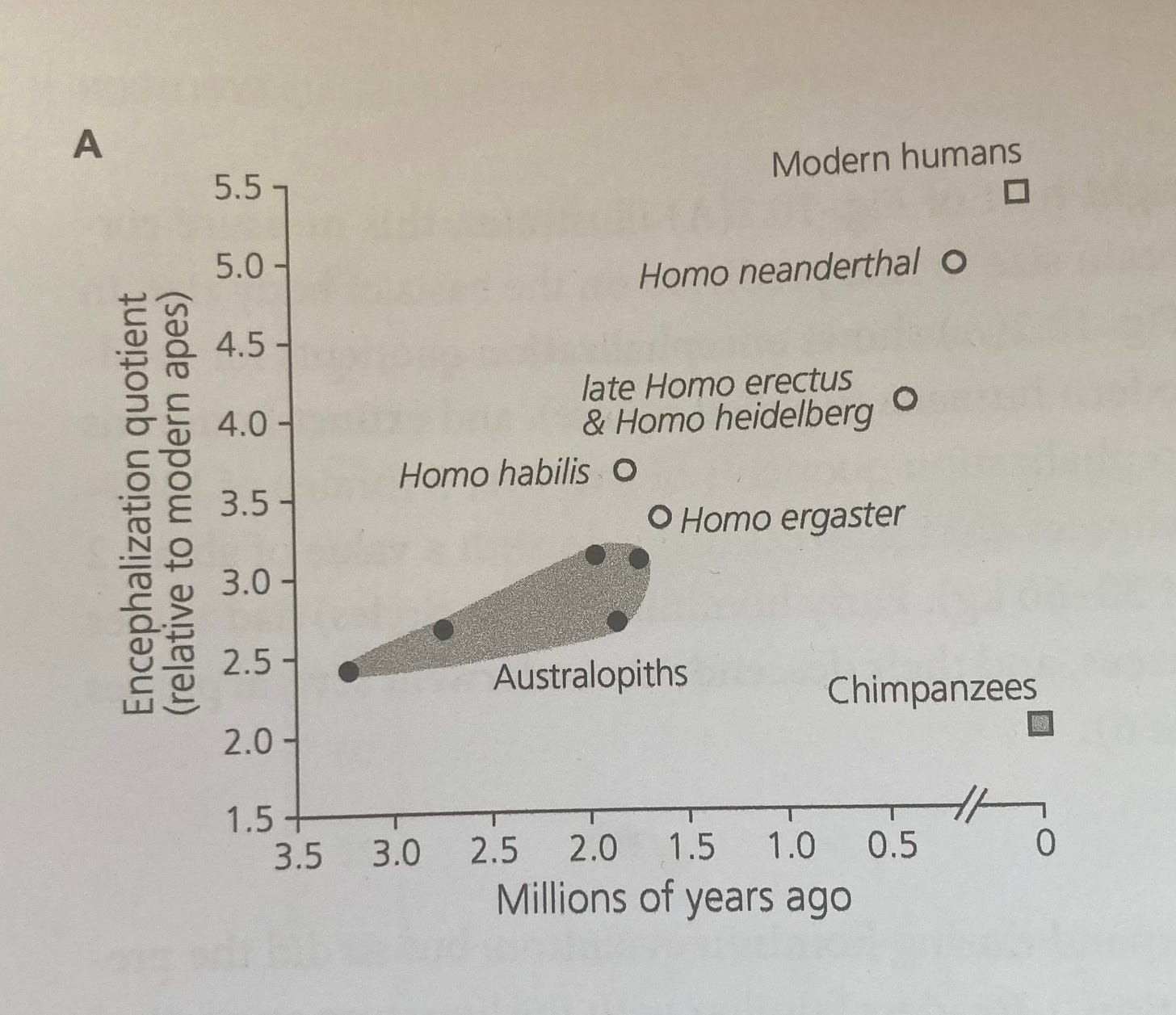

For these developments to occur in tandem would require high encephalisation quotients, and perhaps there was some sort of cut-off that neanderthals never quite reached (see below), although that idea, like much of this field, is highly speculative.

I’ll leave it there for now, although as always I may return in future. If you made it this far, thanks for reading, and if you enjoyed it, feel free to subscribe: