I’m drawing here heavily on the work of Thomas Verny, a psychiatric researcher into forms of memory.

He grew interested in the topic when he stumbled across the Onion-esque headline: Tiny brain no obstacle to French civil servant. Insert your political figure of choice in place of 'French civil servant'.

The takeaway is that huge chunks of the brain can go missing and yet the brain can continue to function. The brain is very adaptive in response to exogenous or endogenous shock (there are debates as to how adaptive it is).

Sadly, we can't really run experiments where we remove parts of the brains of French children at birth and then give them jobs at the Quai d'Orsay to see how they do (bloody ethics committees), but fortunately, plenty of animals and insects go through massive changes to the brain as part of their natural life cycle.

Verny focuses specifically on cellular memory. The memories of many different animals persist in circumstances which would suggest that they should not persist. For instance, planarians are regenerative worms. If you chop up planarians into lots of different pieces, they will grow back to nearly their full size, thanks to a resident population of stem cells (neoblasts). And yet, they continue to retain memory if you do this.

One study involved acclimatising worms to two environments - rough-floored and smooth-floored. Worms naturally avoid light, so when food was placed in an illuminated, rough-floored zone, they didn't go for it immediately. But the rough-floored worms were quicker to go towards the food than the smooth-floored worms. Then the researchers chopped up the worms.

After they'd regenerated, the previously rough-floored worms were then slightly faster to go for the (rough-floored) food than other worms. Interestingly, they didn't do this until their brains had regenerated fully, so clearly the brain of the planaria holds some mechanism for integrating or utilising these memories.

This happens across different species. Bats are thought to have similar neuroprotective mechanisms that help them retain information through hibernation. When arctic ground squirrels hibernate, autophagic (self-eating) processes rid the squirrel's body of anything extraneous to survival, including (RIP) their gonads. Much of the brain disappears, including much of the squirrel's hippocampus, the part of the brain often associated with long-term memory.

And yet, in the spring, they are still able to recognise their kin and remember some trained tasks. Hibernating groups don't do as well as control groups who didn't hibernate at remembering things, but this isn't really a surprise. Also, the squirrels gonads grow back (hurray!).

There are a lot of different results in different squirrel, marmot and shrew studies (all of which seem to happen in Germany, so if you have a pet rodent I wouldn't bring it on your next holiday to Munich) which mostly conclude that these animals can remember things when they return from hibernation.

In insects, similar things happen. Insects, like humans, go through a radical reworking of the brain throughout their life-span. The insect life process runs something like egg - larva - pupa - imago - adult, varying wildly for whichever insect you've managed to trap in your laboratory.

Researchers worked on a species called the tobacco hornworm, and linked a shock with the smell of ethyl acetate (EA). If the larva was exposed to the shock and EA, as a caterpillar, it would try to move away from EA towards fresh air environments. So the learned response is surviving the restructuring of the caterpillar's brain (tobacco hornworms have about 1 million neurons - you have about 100x this many neurons in your gut alone).

And Verny stops off finally, with you. Humans go through a total reconstruction of themselves as they grow to adulthood. Neuroscience researchers are fond of saying things like, "your cortical thickness only decreases as you age". (Also worringly, it may decline more steeply in children of lower socioeconomic status.)

And yet, much of our functionality seems to get better and more coherent as we get older, and we continue to retain memories.

Verny doesn't discuss this, but to make things more complicated, plants also 'remember' things, such as the timing of the last frost.

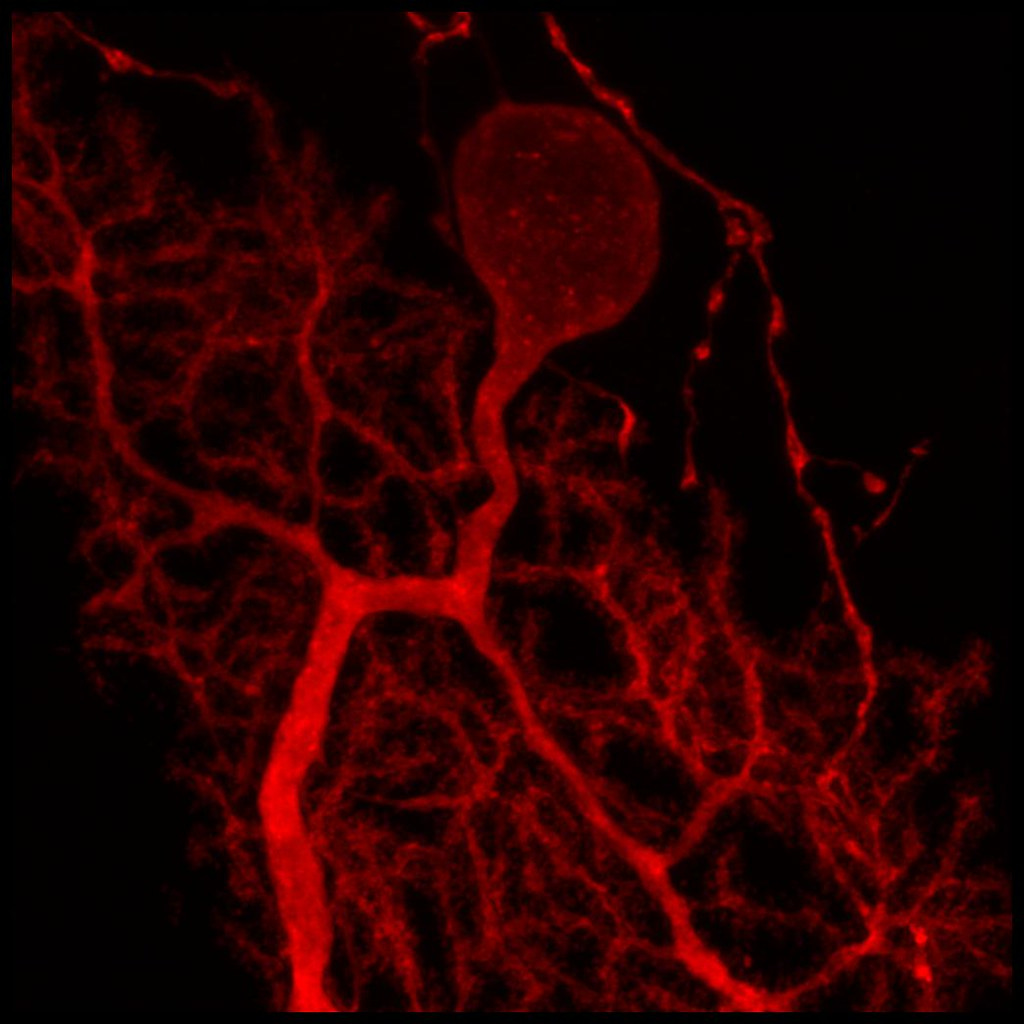

Verny's conclusion is that 'memory', as we understand it, must be partially encoded throughout the body. Indeed, if long-term potentiation, the strengthening of synapses based on patterns of activity, is one of the most important ways in which memory is stored, then how can it not be? I may have misinterpreted this, but it seems part of the problem here is we are still emerging from the era of fMRI scanning when researchers basically tried to functionally localise all brain regions (the hippocampus does memory, the amygdala does fear, etc.).

This is not how any of these regions work; barring edge cases, they mostly seem to deploy a network of brain states in response to a problem. In the functional localiser era, saying that memory is distributed is problematic, but we're very swiftly moving past that to more complex networked understanding of the brain. Verny seems to be tip-toeing throughout this article to avoid the wrath of memory researchers.

And he could go further - the study of memory has focused for a long time on the hippocampus (and more recently the neocortex). But motor memory is mediated somewhere in the cerebellum, a terrifying, mostly uncharted brain region that neuroscientists are afraid to say the name of five times while looking into a mirror.

Part of the problem is that ‘memory’ here is clearly a heavily overloaded term. Different types of memory may be biologically very disparate, and categorising them as ‘memory’ may be holding us back. Clearly memory networks are diverse, disparate and confusing as hell, and understanding them is going to be a long process.

My understanding of all of these things, like life itself, is as ever, limited. Please feel free to contact me if you think I'm wrong.

Verny wrote this to plug his book, so I’ll also plug his book.

Other Random Stuff Section

Been listening to a lot of stuff titled things like ‘Rhythms of Africa’ and ‘Africa: Continent of Rhythm’. The titles feel a bit weird, but the music’s great and underappreciated. I don’t know who Professor Rhythm is or where he completed his doctorate, but I want to meet the guy. His albums are phenomenal. Try out:

Watched Witness last night, where Harrison Ford must live among the Amish to escape corrupt policing. It’s a very enjoyable film, and the director Peter Weir talks about how he sheds lots of the dialogue between Harrison Ford and Kelly McGillis, which makes their interactions much more potent. The silence is helped by that lilting soundtrack that feels like it could go on forever.

Big fan of this on conspiracy theories. Particularly on the use of Gompertzian decay (whatever that is) to model how long conspiracy theories would probably last in the wild. As a general rule, the bigger the conspiracy is, the less possible it is to keep people from blabbing.

.