It is hard to read any significant number of neuroscience studies without noticing that much of the field is doesn’t seem that interested in the actual lived experience of people.

Subjective experiences are much harder to grapple with scientifically. The lack of interest has also been shaped by the history of the study of the mind, which was dominated by psychoanalysis for a long period of time. In turn, psychoanalysis as a field was dominated by one man.

Sigmund Freud features in films, jokes and memes across cultures. Most people have heard of him and at least some of his ideas, such as the tripartite structure of mind, i.e., the division of the mind into id, ego and superego. Importantly, he’s funny. Not that he meant to be. But if you hear about the Oedipus Complex, it’s funny:

Freud was also an early experimenter with cocaine:

“I was suffering from migraine, the third attack this week, by the way, although I am otherwise in excellent health. I took some cocaine, watched the migraine vanish at once, went on writing my paper as well as a letter to Professor Mendel, but I was so wound up that I had to go on working and writing and couldn't get to sleep before four in the morning.”

There are plenty of crackpots throughout history who are funny. Take Serge Voronoff, who transplanted monkey testicle tissues onto the testicles of men as an anti-ageing therapy in the 1920s and 1930s. This didn’t work, before you try anything.

And yet, Freud’s fame persists. That’s because all of these comic theories imply Freud was some kind of wild speculator, stringing together theories of the mind from classical mythology into a theory of why his patients were neurotic.

But there is a Freud that you hear about less because he doesn’t make good meme material. This Freud started out as a neurologist, and worked extensively with nervous systems. He spent a summer dissecting eels in Trieste in an attempt to try and discover where they bred. Today, he might have remained a neurologist his entire life. The reason he didn’t is because the field of neurology was not, in fin de siècle Vienna, robust enough to test his theories.

Psychology has long-struggled with approaches that have been deemed unscientific and irregular. You may have heard of behaviourism, the scientific approach to the mind prominent in the first half of the 20th century, which refused to accept that creatures, be they animal or human, had internality. This approach emerged in response to the dominance of psychoanalysis, the field Freud had pioneered. Behaviourists argued psychoanalysts relied far too much on the internal and the unconscious.

Behaviourism eventually faded from prominence because humans clearly do have internal states and a science of the mind that expressed no interest in these was not the sort of science of the mind that we wanted. We aren’t machines, and our brains do not work like machines.1

A new science has emerged over the last thirty years. Cognitive neuroscience tries to straddle the boundary between molecular and pharmacological approaches to the brain on the one hand, and the broad scope of psychotherapy, psychoanalysis, and hodgepodge other practices that investigate the mind on the other.

In doing so, it has to grapple with the same problem that Freud faced at the start of his career, that ultimately took him away from neurology. In 1895, Freud laid out his ‘Project for a Scientific Psychology’. The opening lines make his strategy clear:

The intention is to furnish a psychology that shall be a natural science: that is, to represent psychical processes as quantitatively determinate states of specifiable material particles and so to make them plain and void of contradictions.

He only gave up this dream over the next few years when he realised that the tools of the trade were not up to scratch. You may have seen the drawings of neurons by Santiago Ramón y Cajal, who perfected Golgi’s neuronal staining technique to map the central nervous system.

He perfected this technique in 1913, some years after Freud had realised that neuroscience was not yet advanced enough to support a truly quantitative science of the mind. There were plenty of neurologists working on the brain at this point, but early 20th century science was nowhere near modelling “psychical processes as quantitatively determinate states of specifiable material particles”.

Freud thought that he could adopt a different strategy. He didn’t really give up on his scientific project. Instead, he began creating theories about the mind from what he could observe - the things people said.

Self-Reporting As A Tool To Get Into The Mind

Neuroscience has a number of tools at its disposal - MRIs, EEGs, PETs, if you can think of a three-letter acronym, someone’s tried to figure out how it can fit into someone else’s brain. All of these have moved neuroscience closer to Freud’s goal of a robust quantitative science of psychology.

Each of these techniques has weaknesses. For instance, fMRIs are temporally inadequate, typically recording data on a timeline of seconds, while neurons are active on a timescale of milliseconds. One way that neuroscientists can get around such weaknesses is to use multiple techniques: “My MRI is good at detecting what this region was doing, but bad at detecting the time that it was doing it? I’ll do another study with EEG to get a more precise temporal view! And hey, even though I’m clearly a diligent scientist, I sure have been written with a weird way of speaking!”2

One tool, used semi-frequently in the past, and then mostly disregarded in the present day, is simply asking people about their experiences. When I began researching for this post, I expected it to be about a clash of values. Hard-nosed, objective neuroscientists, only moved by hard data - coming up against psychoanalysts, arguing that people’s opinions have a value even if you can’t really see them in an MRI scan.

But self-reporting, as it is known, should just be seen as another tool. People’s experiences are just more evidence.

The neuroscientist Mark Solms, working with others, created a new approach to the brain, which he called neuropsychoanalysis. It attempts to reconcile the objective data evinced by neuroscience work with the subjective data that constitutes the body and meaning of our lives. It does so in a Freudian framework, but let’s leave that to the side for now.

In his book, The Hidden Spring, Solms shows immediately that subjective reports have objective value in sense-checking data. The story goes something like this:

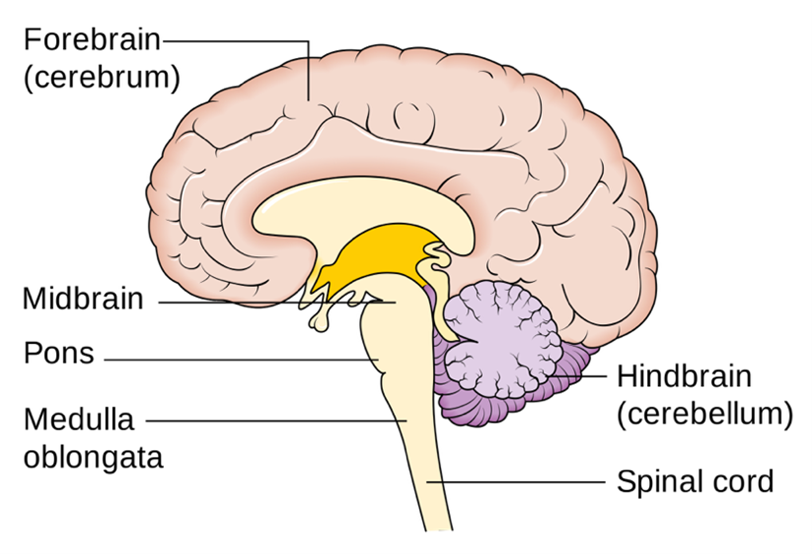

We discovered REM sleep in the 1950s. Through experimentation, scientists discovered that REM sleep was not triggered by the forebrain, but by a brainstem structure called the pons. If you’re not clued up on where that stuff is in the brain, here’s a little schematic:

All the transitions throughout the sleep cycle are controlled down there in the brainstem (everything below the midbrain). The brainstem is often considered a relatively “primitive” part of the brain - the word primitive here just means you see those bits of brain in simpler animals, which don’t share our large forebrains - not that it handles less important things.

We are mostly likely to dream when we are in REM sleep, and since scientists had shown that all REM sleep was controlled down in the brainstem, REM and dreaming could be happily tied together, and dreaming was shown not be a particularly complex psychological process (telling a psychoanalyst that dreaming isn’t a complex process is like telling a bull that you’ve just finished wallpapering his house red).

And there was a motivational angle here - the scientist heading a lot of this research in the 1960s and 70s was Allan Hobson, who was frustrated by Freud and his theories about latent manifestations in dreams. Hobson writes (emphasis mine):

“The primary motivating force for dreaming is not psychological but physiological since the time of occurrence and duration of dreaming sleep are quite constant, suggesting a pre-programmed, neurally determined genesis.”

REM sleep is triggered by a region in the brainstem called the mesopontine tegmentum. If you damage the mesopontine tegmentum, no more REM sleep. But Solms found something else. Patients with damage to the mesopontine tegmentum still reported having dreams.

How did Solms find this out? He asked them about their dreams. We now know that dreams and REM sleep are doubly dissociable, which means you can still have dreams without REM sleep and you can have REM sleep without dreams.

Okay, sure, but how much mileage does asking people stuff about what they see and feel have? Surely to get proper insights, across populations, we need to just run objective studies of brains and compare results? I mean, yeah, true. But you can ask people how they feel while you do that.

It turns out that subjective reports have a lot to offer. Trachtenberg et al. (2025) mention that “neuroimaging studies have shown stronger associations between brain structure and subjective statements about loneliness (e.g. ‘No one really knows me well’) compared to objective social metrics such as number of friends”. Schreiner et al. (2022) write that “contribution of subjective experience will help to elucidate the behavioural and neural mechanisms at play in value-based decision-making”.

Sure, like any good technique for measuring the brain, self-reports have problems. Firstly, they’re hard to measure statistically. But lots of important things are hard to measure statistically: How much does my cat love me? Should I take that job as a windsock salesman? You can use statistics to change the world and you can use it to prove that a dead salmon has brain activity.

Don’t get me wrong, I heckin’ love statistics. But academia over-prioritises science which has gorgeous statistical methodologies, and under-prioritises science that does other things. And just because it is hard to run an ANOVA on an interview, that doesn’t mean that the interview can’t help you interpret the ANOVA you ran on your study.3 Very different things can sit together and hold hands.

Secondly, I think the subjective reporting case is undermined by the fact that people did a lot of it in the past, and generated some weird stuff. For instance, people wearing the God Helmet reported they, uh, felt God. Carl Jung is non-stop wacky:

“On one particular night, Jung had the feeling that there was something near his bed, and he opened his eyes. There, beside him on the pillow, he saw the head of an old woman, and the right eye, wide open, glared at him. The left half of the face was missing below the eye.”

And that’s not even mentioning people talking about taking hallucinogens. But if we ruled out techniques because they’d been misused in the past, statistics would be going the way of Marie Antoinette. A lack of recent scientific interest in self-reports also likely means that there are avenues to be explored that we’re not exploring.

Self-reporting can help researchers gain valuable context for their studies. Chimpanzees are much better than humans at doing short-term working memory tasks. If Person A is much better at working memory tasks than Person B, it is useful to know things like: “Oh, I find remembering the order of numbers easy because I grew up with chimpanzees just like Tarzan”. In a regular study, you might control for this, by recording people’s IQs say, but it is still useful to know.

This could also be considered another problem - you don’t want a self-report to lead the research. But the world without subjective reporting also struggles with human motivations leading the research, and I think we need to just make scientists aware of that and then ask people how they feel anyway.

Self-reporting might also offer you new lines of inquiry, because most of life is weird. Uri Bram writes that once he “went to Kenya and took precautionary deworming pills” and when he got home “he felt 50% less obsessed with my cat”. This generates obvious testable questions.4 Imagine that, but many times over, and in searchable in scientific databases.

Another big draw of using self-reports is that they often by definition examine things that really matter to people. If someone mentions an experience or a feeling or a sensation, it has been raised to their conscious awareness, and so it is likely to be important, at least to them. Many of the things that offer us meaning and comfort in the world are conscious.

Solms again:

“It is our opinion that the subjective experience of what it is like to be a person – the lived reality of individual people, which is the traditional domain of psychoanalysis – cannot be eliminated by any biological model or theory. Simply stated, meanings and intentionality are not reducible to neurons. Likewise, we believe that the systematic study of subjective experience through introspective discourse and through the search for personal meanings yields essential and indispensable data about the structure and functions of the human mind that is impossible to arrive at in any other way.”

It is my opinion that even if you could reduce meanings and intentionality to neurons, it wouldn’t really change the value that understanding them offers us.

As I mentioned above, Solms and other neuropsychoanalytical writers are difficult to read at times, because the field is rife with Freud. A significant part of the project is about integrating his ideas about the mind into the new data offered by neuroscience. There are times when this seems apt, and there are times when this feels forced.

As you read their works, you spend a lot of time watching them link some new piece of neuroscientific research to Freud’s theories. There are times when this is helpful, and Freud can provide a useful explanatory framework. But more often than not, it feels unnecessary, unless you’re already deeply invested in Freudian analysis. To be fair to Freud, he more than anyone wanted to move past the psychological to the objective:

“The deficiencies in our description [of the mind] would probably vanish if we were already in a position to replace the psychological terms by physiological and chemical ones … Biology is truly a land of unlimited possibilities. We may expect it to give us the most surprising information and we cannot guess what answers it will return in a few dozen years to the questions we have put to it. They may be of a kind that will blow away the whole of our artificial structure of hypotheses.

Subjective reports are just another tool in the toolkit for blowing the bloody doors off.

At least, the machines of the past. The reason that neural networks are called as such is because the machines were designed to function as the brain might, rather than the other way around. And even neural networks are naturally a long way from a perfect imitation of brain computation.

At least, that’s how it should work. Often people just publish the first part, where the MRI was successful.

An ANOVA is a basic statistical test and has nothing to do with DJ Khaled.

Perhaps the deworming pills counteract the effects of toxoplasmosis?

There is lots to say on this

For now I will start with Freud...I thought I had read most of the biographies but was delighted to learn that he studied eels in Trieste. When was this?

The oedipus complex...there is a thing...it took me ages to understand that he was not writing a concrete story but using myths to help us understand how we develop our identities in our minds. A way of understanding our mental identity ...in my mind I am like this and desire this or that...