Future Thinking: An Introduction

How to think about thinking about the future

This is the first post in a series on the brain and how it thinks about the future. I will update with more links as more posts are released. The posts stand on their own, but if you want more context or ideas, feel free to visit the other posts in the series.

This Post

Future Thinking: The Default Mode Network

The Yale professor David Gelernter once said:

“My students today are…so ignorant that it’s hard to accept how ignorant they are.… [I]t’s very hard to grasp that the person you’re talking to, who is bright, articulate, advisable, interested, and doesn’t know who Beethoven is. Had no view looking back at the history of the twentieth century—just sees a fog. A blank”.

We all have things we don’t know. And because we have a number of gaps in the things that we know, for many if not most topics, we rely on a series of rapid attribution substitutions that allow us to navigate that space mentally.

For instance, if they have a significant amount of domain knowledge about one area, people often overestimate their ability in other areas, because they assume that similar rules and structures transfer easily to different disciplines.1

One of the classic examples of this is the Nobel disease, where Nobel Prize winners feel qualified to speak in other areas where they lack anything like the same kinds of knowledge that allowed them to make their important discoveries. Take David Gelernter above, who believes that his students are stupid but also has denied evolution and anthropogenic climate change.

Political Alignment

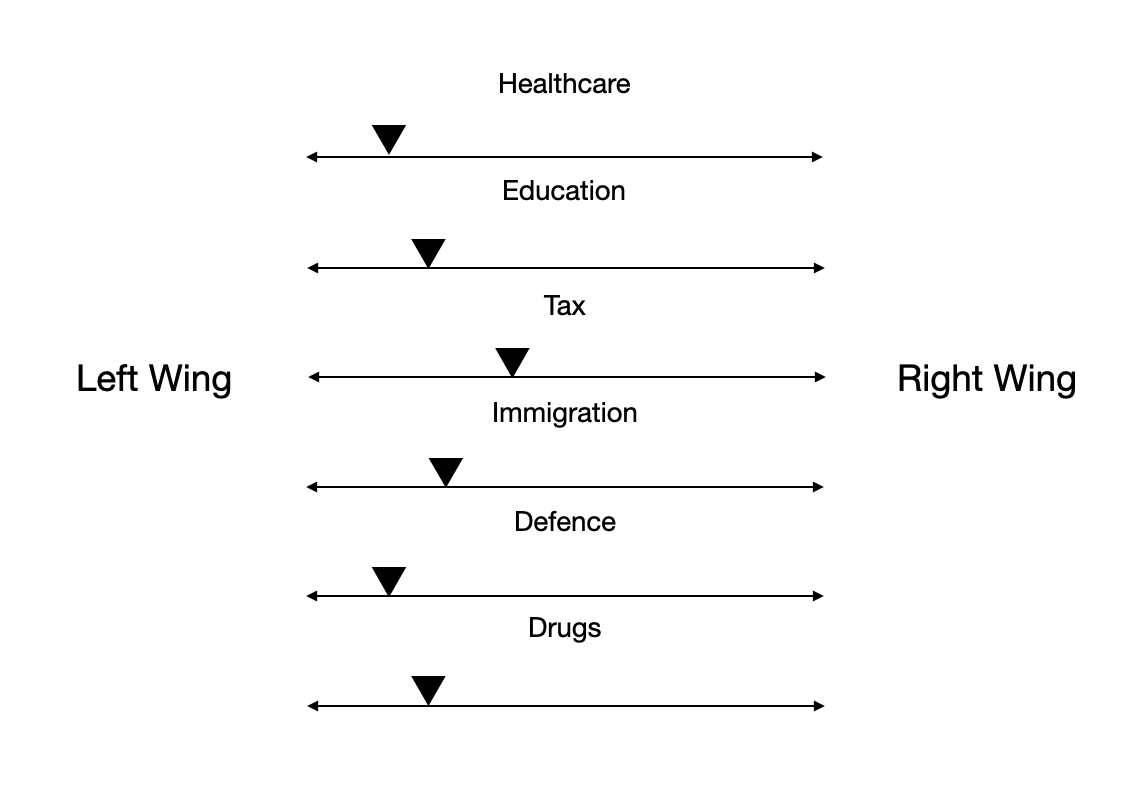

When it comes to politics, people are usually placed along a spectrum from left-wing to right-wing. If we know whether a person is left-wing or right-wing, theoretically, we can use that alignment to predict a person’s set of beliefs. If I know you hold left-wing beliefs about immigration, then I should be able to infer your beliefs about healthcare and drug policy. So if I take a random left-wing person, they should look something like this:

Most people don’t really think about the world like this. Sure, there are some who have really fleshed out and considered their beliefs, but for a lot of people, their opinions aren’t likely to be explicitly laid out like this.2 Instead, they’re likely to just have a sense of what the right thing to do or believe in a certain space is.

And that’s for people who are ideologically coherent. As Davis Shor points out, “the single biggest way that highly educated people who follow politics closely are different from everyone else is that we have much more ideological coherence in our views.”

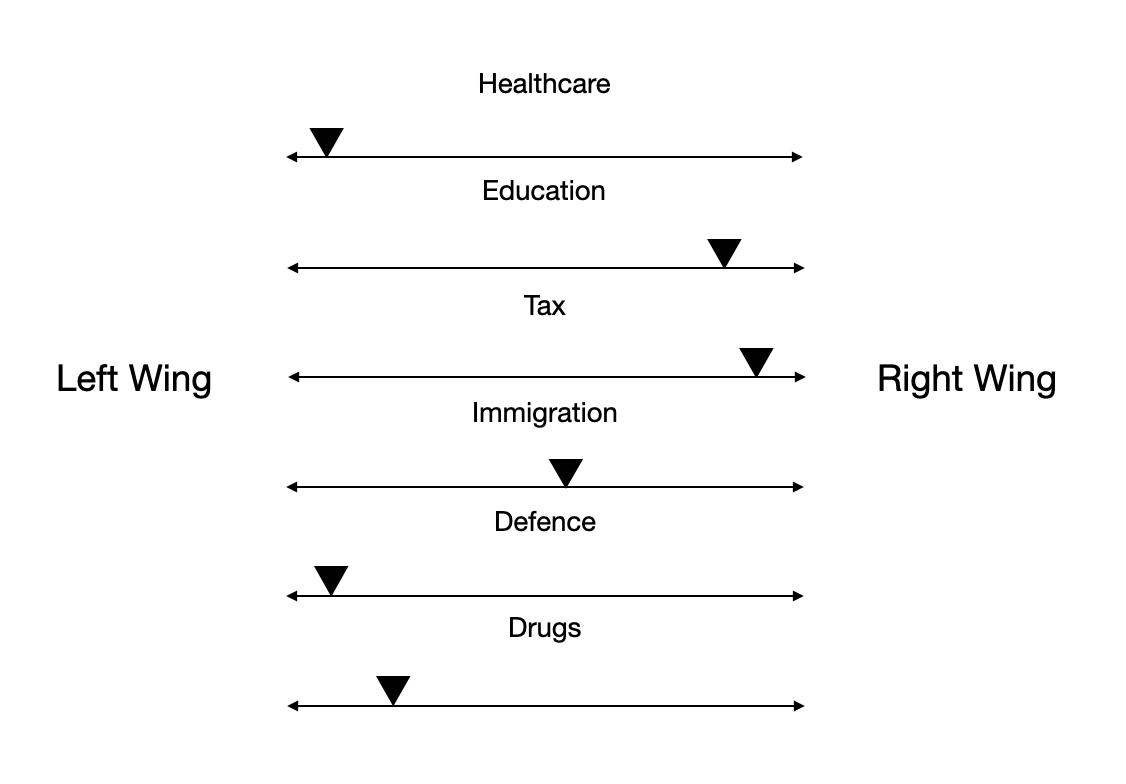

For many people, their views might look more like this:

And these opinions can make little sense when stacked together.3

One of the fundamental issues here is that to hold beliefs that are consistent is demanding. The world contains a lot of granular detail that is evolving constantly, and it would be crazy if anyone could hold onto it all, let alone the main policy perspectives in most areas.

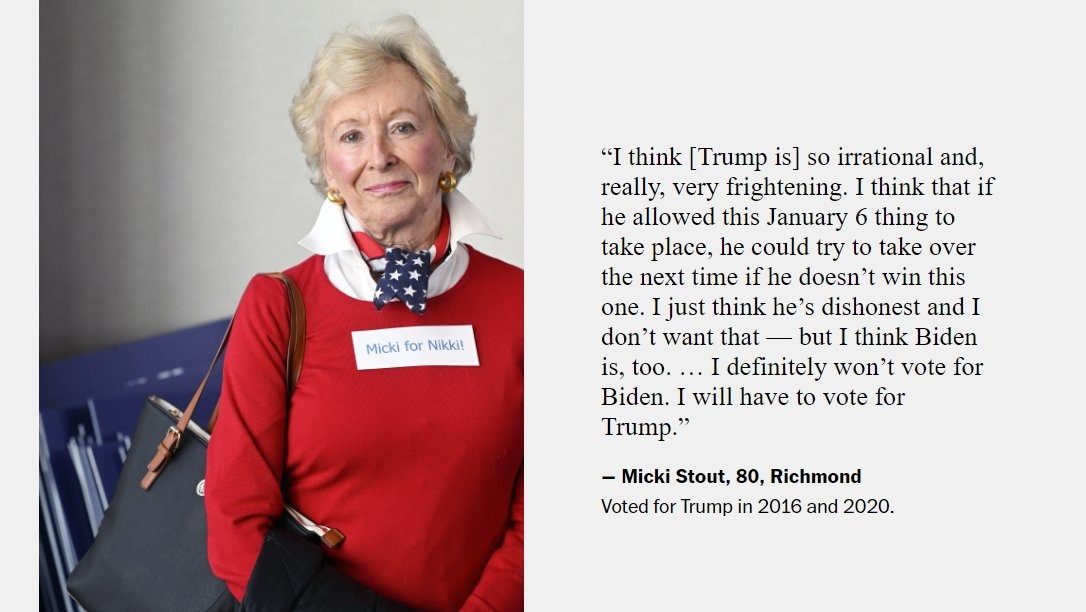

Also people often think like this:

You may be more ideologically coherent than this woman, but like it or not, for most topic areas, you are going to lack knowledge of a lot of the details that matter. And the more informed you are in one space, the harder it becomes to remain informed in another space. Almost all of what we would consider being informed involves relying on the work of others anyway.

I can believe climate change is a real phenomenon without understanding many of its more complicated interactions and feedback cycles. It’d be nice to understand them, but it’d be nice to understand a lot of things.

Not convinced? What if we broaden the range of topics under consideration? I started with traditional political topics, but what if I go more specific? How do you feel about these questions:

What red-team/eval scores for cybersecurity, deception and biosecurity should be required before open-weight or API release for an LLM?

Should polygenic embryo selection be limited to disease risks or should height and cognitive factors be allowed for consideration?

Does the fact that the civil service is meritocratic necessarily reduce its power?

The takeaway here is not that you need to know the answers for these questions (although if you are curious, follow the footnote)4. It’s just that for any given field, there will exist a bunch of difficult questions that are hard to have informed and coherent opinions about.

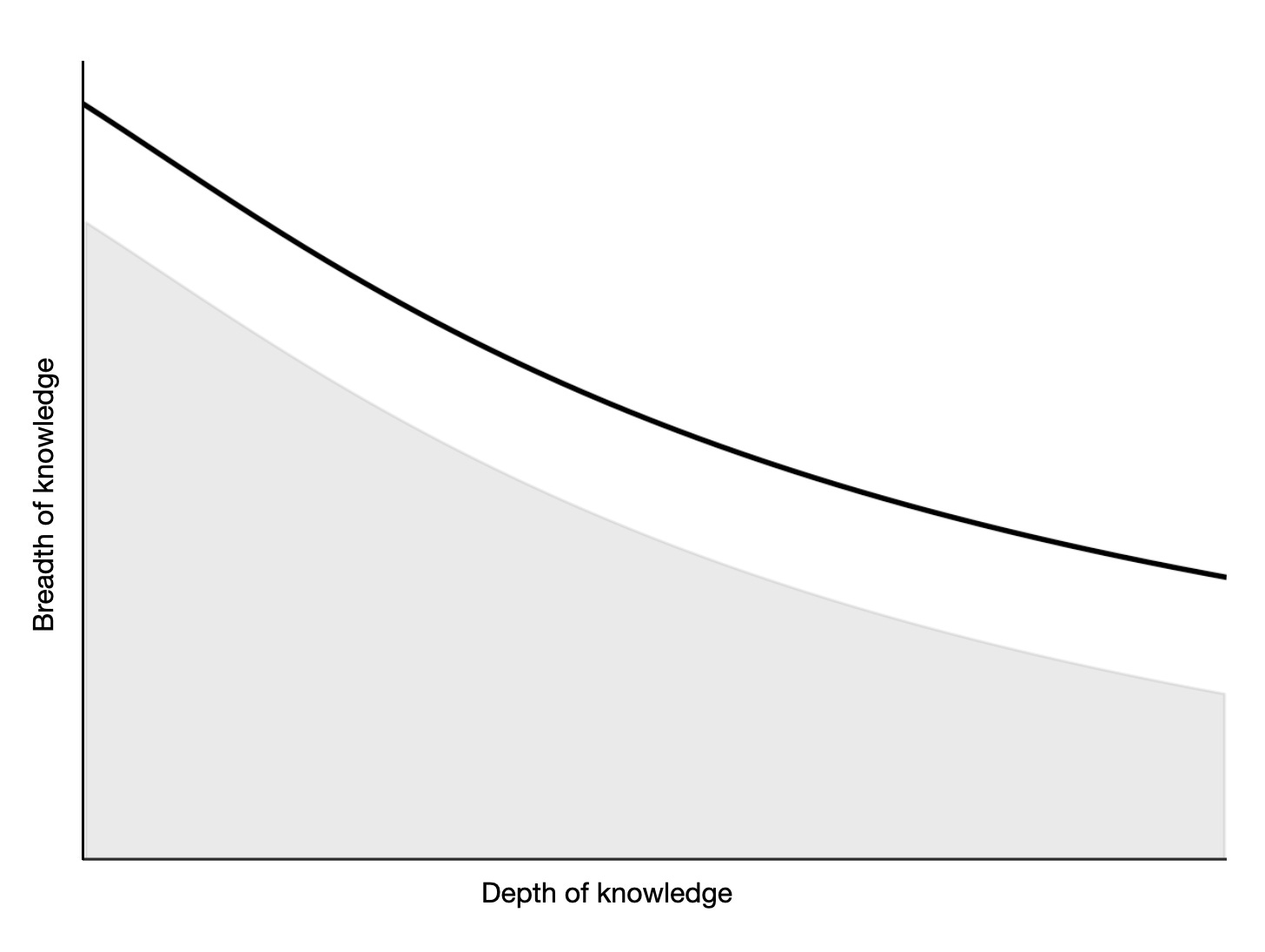

If you like to think in graphs, like I do, you could formulate a Pareto frontier of knowledge about the world that looks something like this:

Since this is all of knowledge, we can assume that no-one is at the frontier except dark sorcerers who have made a pact with Mephistopheles. But everyone is at different spots inside the frontier, in the grey zone, with different breadths and depths of knowledge.

Some may also be surprised to find that when they look into ‘what the left thinks’ or ‘what the right thinks’ on topics where they assume they hold a consensus opinion, their actual beliefs don’t always correlate tightly with their usual political tribe. I don’t want to get bogged down in the politics, but you’re welcome to go away and do that exercise.

All of the above is my somewhat crude way of showing that when we think about the world, we have fundamental structural gaps. I think we’re better off accepting that, as opposed to pretending that we are in fact all experts on Roman wine, quantum geometry and Arabic sex manuals. Obviously we all learn more throughout life, but the world is complicated and changeable and you won’t be an expert on everything at any point. I’m sorry that I had to be the one to break this to you.

Futures on the Brain

Let’s start talking about the future. And to do that, we need to talk about the past. People are interested primarily in memory because it seems to offer the opportunity to make future actions effective. Knowing how to do things, or why things are the way they are, allows people with that knowledge the opportunity to operate more successfully.

How are the procedural memories needed to sink the long-range three pointer stored in Steph Curry’s head and body? How do Renaissance Technologies create algorithms that anticipate short-term movements in the stock market? How do I use the past to actively build the future when I assemble my onions and beans for a chilli I’m going to burn?

If you’re not familiar with terms such as episodic and semantic memory, please feel free to consult my post about the types of memory that we possess.

It turns out that there is heavy neural overlap between the regions of the brain that are active when we’re remembering something and when we’re imagining that same thing in the future.

To zoom in on this claim, Daniel Schacter and Donna Rose Addis (and others) run a study where they asked people to remember things like doing a pub crawl on a holiday in Rome, or playing football with your team Little Apples, or going to a café with your friend Samba for a piadina.

If you then combine some of those randomly, like bringing your friend Samba to a bar in Rome to watch Little Apples play on TV, many of the same brain regions are active as when remembering the actual past (Schacter et al., 2007; Benoit & Schacter, 2015).

People who have deficits in specific facets of memory often struggle to imagine those things in the future. For instance, one patient with episodic amnesia was unable to reliably express what he might do in the future.

But our memories dissociate into various categories, and the same patient’s semantic memory was largely intact. This meant he was still able to reason about the problems that the world might face in the future, which is a kind of semantic projection.

This theory has been formalised by Schacter and Addis in the Constructive Episodic Simulation Hypothesis (CESH). CESH suggests that when we imagine a future event, we dynamically pull details from memory (people, places, objects, emotions) and reconstruct them into a novel scenario.

The neural “overlap” between past and future reflects this process of using memory as a database for imagination. Notably, this constructive process can lead to distortions or creativity – the brain isn’t replaying a file, but actively building a simulation, which is why both memories and imagined futures can blend fact and fiction. The philosophers Denis Perrin and Kourken Michaelian write that ‘to remember simply is to imagine the past’.

The idea I keep seeing unwritten in the literature is that imagination is not really a separate category of thought, although it is often treated as such. Imagination is a term that describes much of the thinking that happens when the Default Mode Network (DMN) is active. The DMN is the network that is used whenever you’re not focusing on a significant external stimulus.

For instance, if you lure participants into a study and then present them with a cross but no task to think about, participants report only thinking about the cross about 10% of the time, and I’m assuming that figure is as high as it is only because people like to tell experimenters what they want to hear.

What’s usually happening is rumination on matters like: “I need to find somewhere nice to eat after these idiot researchers pay me my money”, or “I forgot to pick up Jennifer’s shirt and she is going to be pissed”, or the completely normal, “gosh, that rash on my thigh seems to be growing again”. These sorts of thoughts are generated by the DMN, which I’ll go into more in a future post.

For now you can imagine it as someone leaving the car engine running while they’re waiting to go somewhere. The circuitry is still whirring, but the car is not moving.

Imagining the future is harder work cognitively than imagining the past, because instead of merely generating a simulation of the past, control regions in the brain have to account for the fact that the details being imagined are from different sources, and must mash against each other in a new way (Gerlach et al., 2014; Spreng et al., 2010) So the brain deploys what Benoit & Schacter call the fronto-parietal control network, which modulates behaviour elsewhere in the brain.

For a simple heuristic, imagine that your projections into the future involve brain networks involved in generating the past, with additional brain power being used to control for things that might be different in the future, such as the addition of flying cars or the fact you’re now in love with someone with Parkinson’s disease.

But remember, you don’t just get these additional details for free. The brain must simulate them. And this is hard work, because reality has a lot of detail and you can’t really anticipate all of it.

This is why people are often bad estimators of how happy they will be in the future. Cognitive work is hard and the brain doesn’t like doing it, so the harder it is to imagine these scenarios, the less likely you are to do it.

It is very difficult to imagine what it is like to have a child because it is a multifaceted event that has implications for a lot of your life. On the other hand, it is much easier to imagine what it’s like to own a flying car because the brain can just imagine flying cars doing what regular cars do now, but in the air.

Making the Future Easier by Simulating It

In the show Devs, the quantum computing firm Amaya are working on a computer powerful enough to simulate all known history. In one scene, we see a grainy projection of Christ, as the machine sees him, living history rendered from silicon.

If you’re a strategy person at a large company, you have to think about what your company will be doing in a year. And three years. And five years. And perhaps even fifty years. This involves simulation. You have to imagine what it might be like to be working for your company in three years, and how you will handle challenges that present themselves. The trouble is that you don’t know what any of these challenges are or what your company will look like, and you don’t have the world’s most powerful quantum computer to hand.

This is a big problem. You want your company to be successful, and you know all of the adages about the best time to plant a tree being twenty years ago and the second best time being now. But you don’t know what sort of tree to plant, where to plant it, or whether the world of 2050 will be a good place for acacias or pines. Any time you run those simulations, as we discussed above, you will have large gaps, because you have not yet traded your soul to Mephistopheles for infinite knowledge.

The reason I discussed the gaps in human knowledge above at length is because I want to cement the idea that for any of those gaps, there is a high chance that when anticipating the future, you will gloss over the importance of that information.

The brain’s predictive network is very strong. This means that if it sees things that it thinks it can easily predict, it often ignores much of the detail and guns straight towards making a prediction.

You often don’t use very much new information to reason about the world. Instead, you rely on a set of strong predictions about the world, and twist and tamp them in response to a small percentage of incoming information. When we’re thinking about the future, it’s very easy to allow the mind to fill in gaps with imperfect present knowledge that has little bearing to a future world.

Futurists have been working on this problem for a while, and one answer they sometimes propose is that the future needs more detail. When you’re working on the future, you should be actively creating details of the future. What does the world you’re imagining look like? It’s useful to flesh that world out with real situations or concepts. Ideas from the present world will exist in 2050, but they may only be nascent now, or they may be dominant ideas now which have been recast in different forms.

There are ways that seem to improve prospection, or to improve it in the way we care about. For instance, Schacter et al. (2017) discuss a procedure called Episodic Specificity Induction, which involves training people to focus on elements of past experiences. This can dissociate semantic from episodic factors in memory, and seems to help with future planning:

Recent evidence indicates that administering the ESI procedure described earlier just before individuals simulate possible solutions to personally worrisome future events has beneficial effects on emotion regulation: following ESI versus a control induction, participants generated more constructive steps to address a future worrisome event, were better able to reappraise the event, and showed improvements on several measures of subjective well-being.

This is where I’m going to stop for now. This is the first part in a longer series on thinking about the future, which is going to take this rough format (but maybe not in this order):

Introductory post <- You are here

The Default Mode Network and the future in your brain

What does the divide between episodic and semantic memory mean for thinking and the future?

What tools do future thinkers currently use and how effective are they?

What is to be done about future thinking?

Thank you to Andrew, Sue, Joel and Aidan for notes on this post.

Sometimes they transfer more easily. Statistics is unreasonably powerful in a number of different fields. But there are still dangers to deploying statistics without thought to a new field that can be easy to miss.

I would add that the process of fleshing out your beliefs usually creates ambiguities rather than alignment.

If you’d like to read more about this phenomenon in political thinking, David Broockman’s piece on Applying Policy Representation is very interesting.

Some jumping off points, for the very curious: On red-teaming, on Using Polygenic Scores to Select Embryos and the Epistemic Value of Gain of Function Experiments.