Future Thinking: The Default Mode Network

A normal mode of brain functionality that supports future thought

This is the second post in a series on the brain and how it thinks about the future. I will update with more links as more posts are released. The posts stand on their own, but if you want more context or ideas, feel free to visit the other posts in the series.

This post

In Jennifer Gidley’s The Future: A Very Short Introduction, there is a section when she laments the image of the crystal ball being used to represent the work that futurists do. There are many ways that humans have tried to divine the future, from the Ancient Roman haruspex who would sift through animal entrails to determine the will of the gods, to the Ifá divination system of Yorùbá-speaking areas of West Africa.

Gidley’s concern is that the crystal ball implies that any attempt to understand the future must inherently be ascientific. And yet, the work of looking at the future is critical, because we’re desperate to know it. We build models, we construct forecasts, and when all of that fails we ask an octopus for the results of football matches.

It is also nigh on impossible. Even in systems where the capricious agency of humans is less of a factor, such as weather prediction, progress in predicting future patterns has been slow.1

And yet, one of the things that few futurists seem to have done is to consider information from neuroscience about how humans think about the future.2 On the other hand, many neuroscientists are content to study how the brain models the future without using that information to influence decision-making processes.

The brain is likely to place constraints on the way that we make decisions about the future. These constraints may be fundamentally rooted in the way the brain works, or they may be flexible products of the way that we are acculturated and educated. They may be rigid or they may be malleable.

This series aims to shed light on some of those processes. What undergirds decision making about the future in the brain? How do humans combine information to make choices about future rewards? This is a huge field, and I’m hoping to sketch out the contours rather than to comprehensively cover everything. But it is an important field, because modelling the future is vital.

This post explores a key brain network involved in imagining and simulating the future: the Default Mode Network.

The Greedy Brain

The brain is an energy hog. This was discovered in 1948, when Seymour Kety and Carl Schmidt began to measure whole-brain blood flow and metabolism in humans, and discovered that although the brain represents only 2% of body mass, it uses 20% of the body’s metabolic energy.

Kety and Schmidt took these measurements from humans who were not doing anything - they were in what is now known as the resting-state.

In 1955, after Kety and Schmidt had thought about it for seven years, they had subjects perform a difficult mental arithmetic task. Surprisingly, asking subjects to do hard mental work had very little impact on blood flow or oxygen consumption in the brain.

On first glance, this doesn’t really make sense. If you wanted to roll a pebble up a hill, it takes a small amount of energy, and you’d probably do it by yourself. If you wanted to roll a boulder up a hill, it takes a lot more energy, and you’d probably hire Sisyphus as a contractor. These are fundamental laws of physics.

But the additional energy consumption associated with changes in brain activity is very small, often causing energy use to fluctuate less than 5%. So the brain’s energy budget is affected less than you might think in response to the tasks it is engaging in.

One explanation for this is that the brain is already doing a significant amount of processing, even before we lump it with tasks that we would consider cognitively difficult. As early as 1914–15, the mountaineer–physiologist Thomas Graham Brown argued that much important neural activity is intrinsically generated. In other words, much important brain activity is self-generated, rather than being a response to things happening in the world.

More recently, researchers have unravelled some of the mysteries of this internal brain activity, finding that a significant proportion of it is in a brain network known as the Default Mode Network (DMN).3 The DMN plays a role in a long list of tasks, mediating, among other things:

self-reference

theory of mind

moral reasoning

episodic memory

social judgements and evaluations

remembering the past and thinking about the future

As Azarias et al. (2025) put it:

The internal mental activity hypothesis, also known as spontaneous cognition, is a theory that describes the role of the DMN in the generation and manipulation of internal thoughts during periods of rest and introspection… …According to this theory, when individuals are not engaged in external or externally directed tasks, the DMN becomes active, facilitating reflection on the self, the retrieval of personal memories, the mental simulation of past and future events, as well as the planning of imaginary scenarios.

As I’ll explore more throughout this post, the DMN is a central component of how we simulate and imagine the future.

The study of the DMN goes back to Shulman et al. (1997), who first noted using PET scan analyses that a number of areas in the human cerebral cortex consistently reduced their activity while people performed tasks with three important dimensions: (1) they were novel, (2) they were unrelated to the people performing the task, and (3) they had a clear goal.

We’re focusing on those areas that were reducing their activity. These areas are now considered part of the DMN, which is engaged actively in processing tasks that aren’t novel, that are self-related and that don’t have clear goals.

So when presented with those tasks involving those dimensions, these areas reduce their activation. Marcus Raichle coined the term “default mode” in this heavily cited 2001 paper to describe these areas.4

The DMN is a large brain network with numerous nodes, and some of its key functional hubs have some of the highest metabolic rates in the brain, which may be why diseases like Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s often target the DMN.

And the DMN doesn’t work alone, as Azarias et al. write:

However, the DMN does not operate in isolation but interacts dynamically with other large-scale brain networks, enabling the brain to adapt to varying emotional and cognitive demands.

For instance, the DMN often activates in co-ordination with other areas of the brain, such as the frontoparietal network or control regions located there.5

The DMN and the Future

I’ll discuss how the DMN is structured in a second, but for now let’s take a slightly cursory approach. Thinking about the future is obviously a multifaceted process, so let’s walk through some of those facets.

Firstly, key hub regions of the DMN seem to support rumination about the future, which takes the form of simple mind-wandering.

Picture this. You’re lying on your bed and you’ve just woken up. The half-light of the room bleeds in through your blinds. What are you thinking about?

A list of errands might be scrolling through your head; stuff you have to do today, tomorrow, this week. The DMN is active as you think about the fact that you need to return Joey’s umbrella, which present you need to get Chandler for Christmas, and your more amorphous plans to try to move into Monica’s rent-controlled flat. I take this form of loose, deconstructed future planning to be one of the primary modes of the DMN.

Secondly, the DMN also seems to support systems in the brain which determine the value of future rewards. Let’s say you are offered the choice of a reward now or a larger reward at sometime in the future. How do you compute the optimal choice?

Humans usually have a relatively high discount rate for future rewards, which means they prefer rewards that come quickly. This makes sense, because distant future rewards have a large opportunity cost wherein you can’t use the reward until you get it. For instance, you can’t invest money you don’t currently have, despite what the scammers who regularly text me suggest is possible. Activity in key hubs of the DMN thus seems to underpin the way we make decisions about the future.

We can also seemingly influence that activity by encouraging people to focus on specific elements of those decisions. For instance, people discount future rewards less when the reward is going to arrive on a specific date, like the 27th January 2026, rather than when the reward is going to arrive after a unit of time, like 30 days.

We can also change people’s discount rate by increasing the amount of decision time, or by expanding the sensory richness of alternative options, especially when compared to options that have benefits in the short-run. It’s highly plausible that we influence the way that decisions are discounted based on the information is provided around that decision. This information can take multiple forms, such as abstract details, sensory influences, and spatial location.

Peters & Büchel (2010) had subjects think about specific future events while making choices, and found that this changed the way that the brain made decisions. Providing sensory-rich, personal detail about the future engages different circuitry in the brain, such as associative memory circuits in the DMN, which in turn can encourage people to rebalance their priorities towards longer-term outcomes.

Thirdly, David Wolpert talks of memories as retrodictions (essentially a set of highly precise predictions about the past). Thoughts about the future are built on top of these, using those memories to fill out predictions about possible future states.

Accordingly, remembering the past and thinking about the future use similar brain regions, albeit with future thoughts relying on additional frontoparietal control regions in the prefrontal cortex that support the fact that new details must be generated.

One possibility is that the default mode network supplies much of the raw material for an imagined future (in doing so it draws on memory-related regions, including the hippocampus). Control regions might help to shape that material by keeping the goal in mind, selecting what’s relevant, and enforcing constraints so the simulation stays coherent and plausible.

Additionally, the DMN activity of two individuals seems to become synchronised when they process shared narratives, with this synchronisation being particularly selective to shared social cues. Inter-individual synchronisation in the DMN seems to be related to social proximity, as this study from Hyon et al. (2020) suggests.

This suggests information which comes from people you trust more is more likely to influence your own behaviour, although that Hyon et al. study doesn’t show whether friends become friends because their brains process information similarly, or if interacting over time makes their neural activity align, and both may be true.

The Structure of the DMN

It may help to break down the structure of the DMN a little, even if this may get a little more technical.

A series of papers examined key functional hubs of the DMN by collecting Resting-State Functional Connectivity (RSFC) data from functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging.6 RSFC data looks at spontaneous brain activity, showing how different brain regions’ blood-oxygenation-level-dependent (BOLD) signals fluctuate together over time.

Neurons lack reserves of things like sugar and oxygen, so when they fire, energy has to be brought in quickly. Blood releases oxygen to active neurons at a greater rate than to inactive neurons, because if you’re active you need more fuel, in the same way that a professional gamer in an E-Sports tournament needs to drink more Red Bull than they would otherwise.

Oxygen-rich blood has a stronger effect on magnetic fields, and brain regions use more oxygen whenever they are engaged in a given task. This means you can track whether brain regions are active during a task by whether an MRI machine picks up more magnetic field strength from these brain regions during that task.

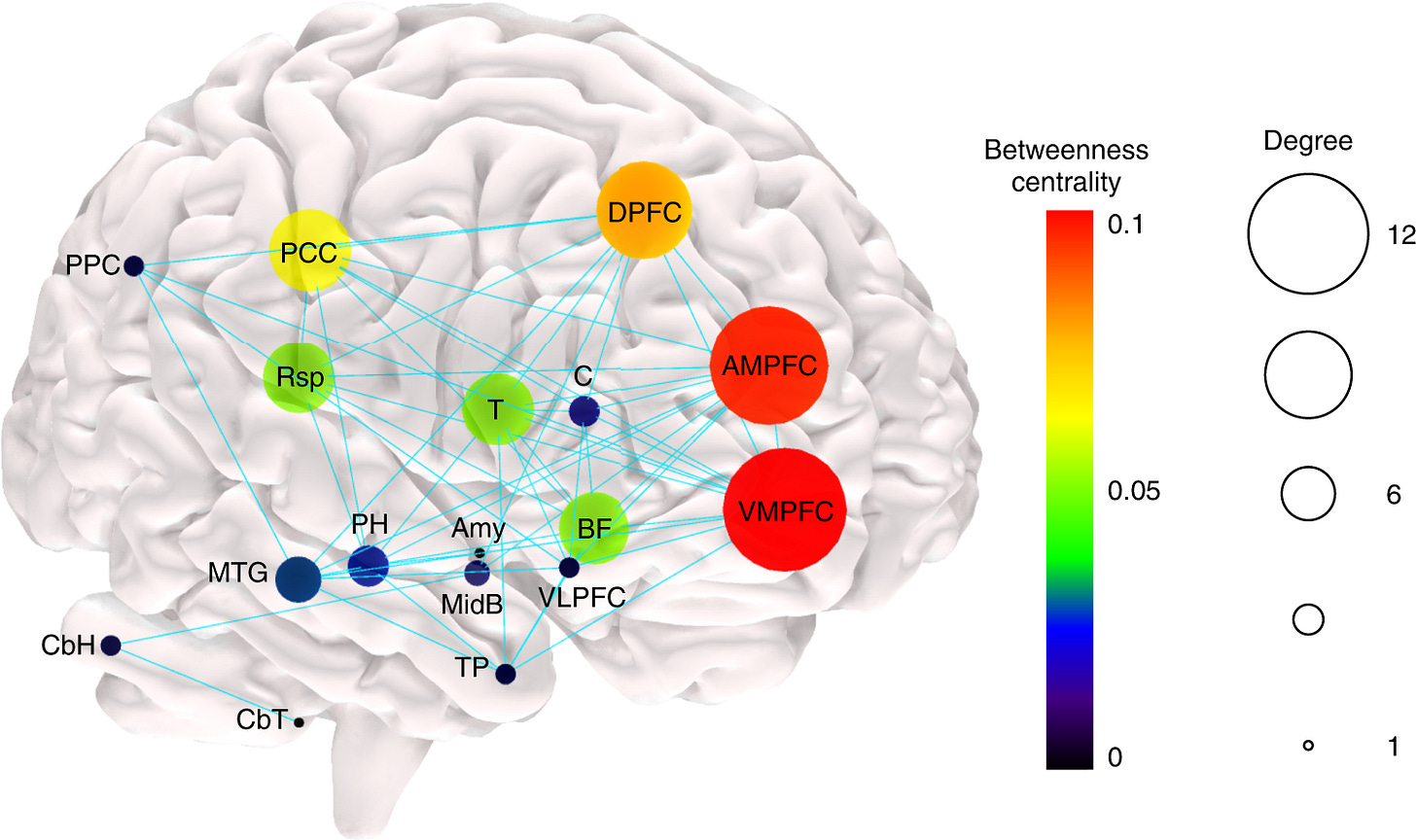

The DMN is the network of brain areas that have a high baseline activity in the absence of strong external stimuli. As I mentioned earlier, it contains a number of major hubs.

These include the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC), which is involved in thinking about oneself and the future and is located towards the front of the brain. Other major hubs include the posterior cingulate cortex (PCC) and the precuneus, which are involved in recalling memories and context, and are located towards the back of the brain.

The angular gyrus (in the lateral parietal cortex) also plays a role, as well as medial temporal lobe structures (including the hippocampal formation). I never find it particularly useful to just list out brain regions that do things, so let’s use a picture to try to get a clearer sense of what’s going on:

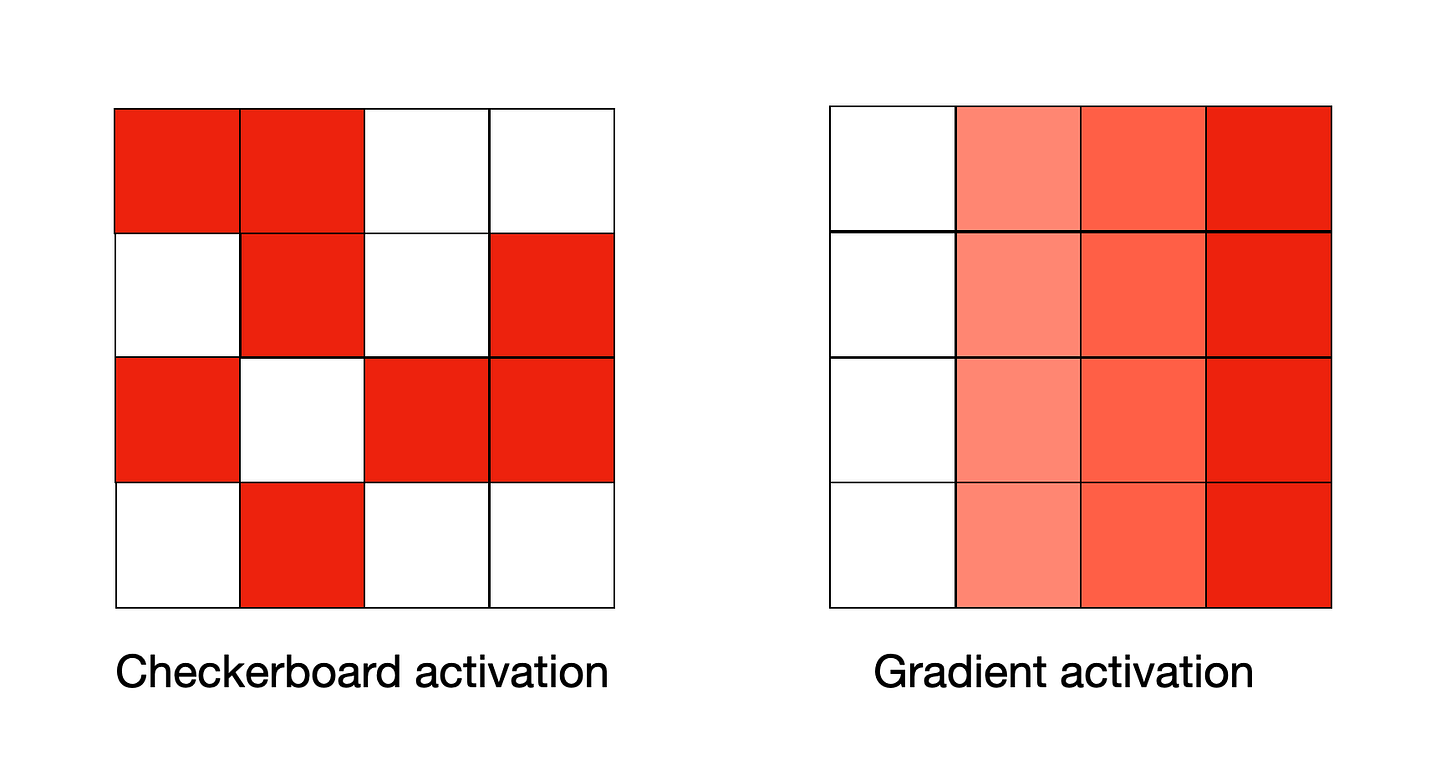

There are a lot of interactions going on here! I’ll stress again that this is a large and complicated brain network. Two terms from the paper are worth defining to help you understand the image:

Node degree refers to the number of connections between a given node and the other nodes of the network. Betweenness centrality is the fraction of all shortest paths in the network that pass through a given node.

In other words, the AMPFC and the VLPFC are highly connected nodes which commonly feature on a particular shortest path between two brain regions. However, all of these nodes are important. When people talk about “DMN activity,” they are broadly referring to strong coupling among all of these regions when participants are in a resting-state.

They also are referring to increased activation relative to baseline during internally focused cognition. The DMN often reduces its activity during attention-demanding, externally focused tasks, but it is not necessarily only active during stimulus-free states.

But usually, when presented with a strong external stimulus, key nodes of the DMN are suppressed in order for our brain to process that stimulus.

The DMN was previously referred to as the “task-negative” network, but this is misleading, because it suggests that the DMN is engaged in mostly passive activity. As I’ve previously discussed, the DMN uses a significant amount of energy, and is engaged in performing critical inference across a number of domains.

Moving Along the Abstraction Gradient

It is possible to imagine the brain as processing information on a gradient, where it recruits different regions in response to the level of external stimulus it is currently processing.

So, if you’re deeply immersed in an external task, then it follows that brain regions which handle external stimuli will be more active. If you don’t really have a task on the boil, you might see more activation of the DMN and other processes which are anchored in internal inputs, such as memories.

Paquola et al. (2025) explain:

Although the DMN is typically defined on functional grounds (that is, strong resting-state functional connectivity and relatively lower activity during externally oriented tasks), its subregions are also connected by long-range tracts and each subregion is maximally distant from primary sensory and motor areas.

This topography may allow activity in the DMN to be decoupled from perception of the here and now, as neural signals are transformed incrementally across cortical areas from those capturing details of sensory input toward more abstract features of the environment. These observations suggest neural activity in the DMN has the potential to be both distinct from sensory input, while also incorporating abstract representations of the external world.

So brain processing may take place along a gradient, with some areas processing more concrete phenomena which respond to sensory information while others respond to more abstract phenomena. In vision, signals flow from basic feature detectors at the back of the brain to more abstract object recognisers further forward. Similarly, the frontal lobes seem organised from concrete action control in the back to broad goal planning in the front.

These patterns may also not appear as gradients in cortical structure, as Paquola et al. point out that some areas experience interdigitation of different forms of activity, meaning that the same area may respond to sensory data or abstract data in a checkerboard pattern.

This notion was originally proposed by Buckner and Krienen (2013), who called it the “tethering hypothesis”. They argued that areas of cortex which specialise in creating associations between different modalities can be found at increasing spatial distance from brain areas which focus on processing sensorial information (sometimes termed primary cortex).

This is further reinforced by the fact that areas of unimodal cortex (i.e., parts of the brain focused on a specific sensory modality) have tightly coupled structure-function maps, meaning that you can easily predict the function from the structure. On the other hand, transmodal or associative cortex (i.e. cortical areas focused on combining information from different sensory modalities) show more divergent connectivity.

Much of the way that we process options about distant futures is likely to take place in these areas of associative cortex. There may be a link between the way that we make decisions about what rate of discounting to place on a decision, and the areas of the cortex in which such decisions take place.

Decisions about future tasks probably take place along a spectrum of complexity, because some tasks are simple and some are more complicated. Returning an umbrella to Joey is relatively easy. Buying a present for Chandler requires integrating information about him and his preferences and your previous relationship with him.

Moving into Monica’s flat requires doing all of that and then combining it with semantic information you don’t know - what the rent is likely to be, how you’d then split it with her, what she’d be like to live with (terrifying!) and so on.

If the crux of the “tethering hypothesis” holds, it would suggest that relying solely on abstract information in decision-making processes may privilege different sets of results to alternative methods. I’ve been doing some work with futurists on what forms these alternative methods may take, and I’ll discuss them in a later post.

So, to recap. The core idea that the DMN underpins key circuitry around different ways of imagining the future is well-supported in the literature, although some of the rest of what I’ve written here is more speculative. The next post will examine episodic and semantic memory, and how the brain uses these different forms of memory in supporting argument and in simulating the future.

Thank you to Andrew, Sue, Joel and Izzy for notes on this post.

Although it has consistently improved over the last few decades.

There are a few exceptions I should highlight: Maureen Rhemann’s Deepening Futures with Neuroscience, Maree Conway’s Exploring the Links between Neuroscience and Foresight, Faiella and Corazza’s Cognitive mechanisms in foresight and Jorge Camacho’s Naturalising futures sensemaking.

It is sometimes known as the Default Network, but we’ll stick to calling it the Default Mode Network.

For a rich history of the study of the resting-state of the brain, see Snyder and Raichle (2013).

The DMN is also sometimes broken down into smaller sub-networks, and you can read Andrews-Hanna et al. (2010) for more on this.

Here I’m drawing on a combination of Yeo et al. (2011), Choi et al. (2012) and Buckner et al. (2011).